The Aurochs

This is a guest article, kindly contributed by Daniel Foidl, an Austrian law student and Palaeo-enthusiast. Daniel is the creator of the long-running Breeding-back Blog, a site dedicated to exploring the process of restoring extinct fauna via selective breeding of their domesticated descendants. Additionally he is an amateur palaeo-artist, whose work you can view at Deviantart.

The aurochs, Bos primigenius, was the wild ancestor of domestic cattle that became extinct as recently as 1627. Habitat limitation and hunting sealed the fate of this wild bovine as human civilization expanded. Its extinction was the first disappearance of an animal to become documented by humans.

Anatomy and life appearance of the aurochs

Numerous well-preserved skeletons, skulls and other osteologic remains in- and outside Europe tell us about the morphology of the wild ancestor of cattle. It was a large bovine – van Vuure (2005) gives an average withers height of 160 to 180 cm for the males and 150 cm for the females (1). The maximum size for males might have been 200 cm (2). A huge skull kept at the British museum of London with a length of 91,2 cm suggests a very large size (2). Pleistocene (2.58 mya to 11.7 kya) individuals were on average 10 cm larger than Holocene (11.7kya to present) specimen (1).

The aurochs differed drastically from cattle in proportions. It had a shorter trunk and longer legs so that the shoulder height equalled the trunk length (1). Also, the head was larger and more elongated (1). What is also an important difference between aurochs and cattle is the fact that the shoulder spines are considerably higher in the aurochs, forming a “hump” as it is seen in other wild bovines (1). Contemporaneous artistic depictions, such as in the famous cave paintings of Lascaux, Chauvet and Altamira, suggest that it had a short dewlap and a barely visible udder in cows. In extant wild bovines the udder is very small as well (1).

Also the colouration of the aurochs is known. Coloured cave paintings and historic descriptions of living aurochs and a hide from the 16th century (which was in possession of Sigismund von Herberstein) suggest one and the same colour. As it seems, aurochs bulls were of a black colour with a narrow, lightly coloured dorsal stripe and cows of a reddish brown colour (with darker areas on neck, face and legs). Both sexes also probably had a lightly coloured muzzle ring that might have been reduced to a white chin in some individuals. Calves were born in a reddish brown colour and male individuals turned black in their first year, as described by Anton Schneeberger in a letter to Conrad Gesner in the 16th century (1).

The aurochs did not have a beard like the wisent, Europe’s other wild bovine, but it had frizzy curly hair on the forehead. These prominent forelocks have been described in historic accounts. There were belts made of the skin of the curly forehead of aurochs (1).

The most impressive body parts of this bovine where its large horns, whose bony cores could reach sizes of up to 120 cm in length (2). In life, surrounding keratin would add to the length and diameter of the horns. Those of bulls were larger and thicker than those of cows on average (1). Although the horn size varied from individual to individual, the basic curvature of the horns was always the same. They curved out of the skull similar to a spiral, which is why the aurochs horn curvature is described as “primigenius spiral” (1). Basically they started to grow upwards and outwards, then forwards and then inwards and upwards at the tip (1). The base of the horn was thick while the tip was slim and pointy (2). Preserved horn sheaths as well as paintings of ornamented aurochs horns show that they were of a light-yellowish colour with a dark blackish tip (2). All in all the aurochs must have been a swift and agile animal, as historic accounts mention the speed and agility of the bovine (1). It is also recorded that it could become very hot-tempered and aggressive when teased (1).

Fig. 1: Life reconstruction of an aurochs bull, based on the Preljerup skeleton © Daniel Foidl

Fig. 2: Life reconstruction of an aurochs cow, based on the Sassenberg cow skeleton. © Daniel Foidl

Distribution, habitat and ecology

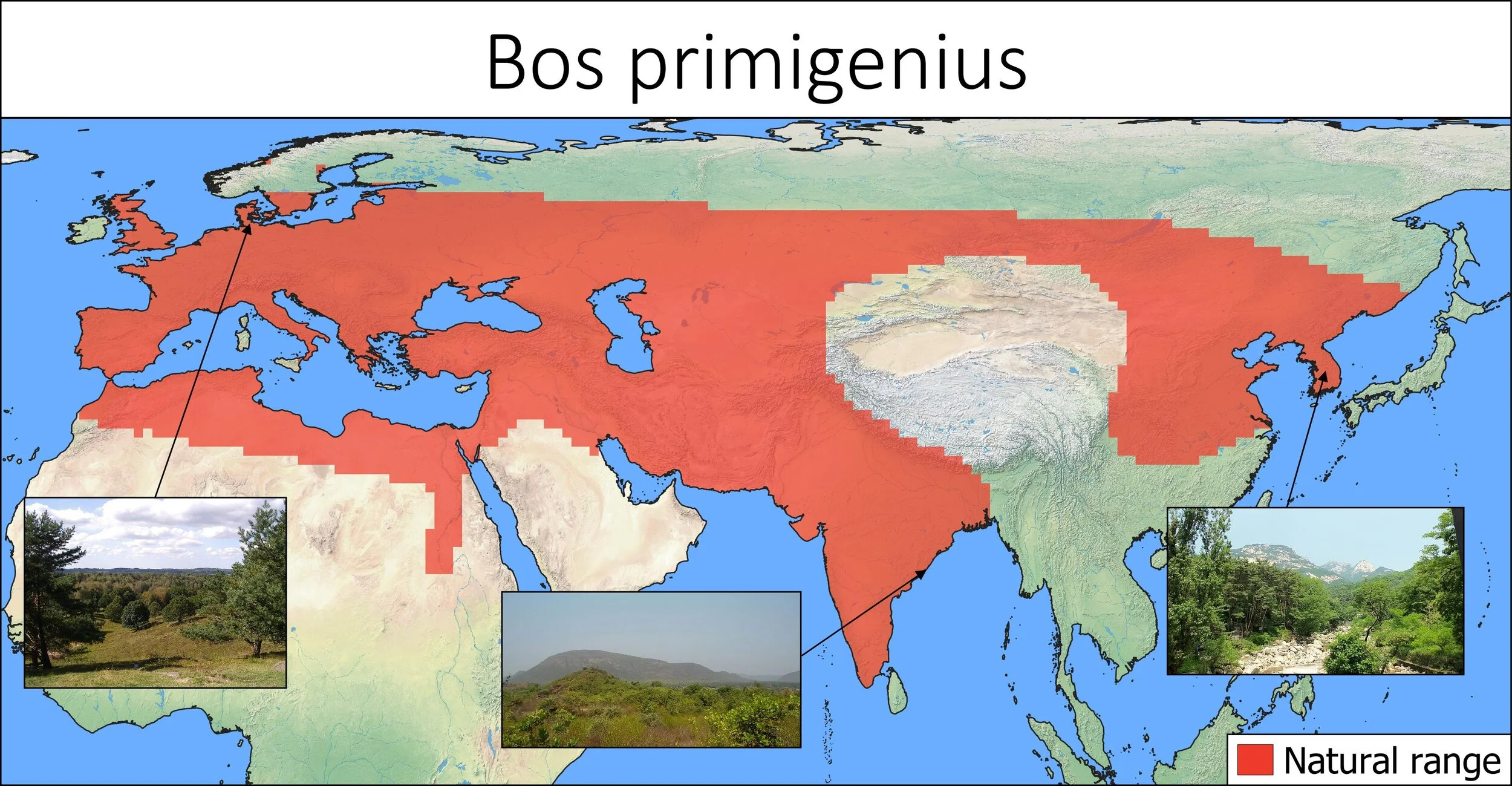

The earliest record of Bos primigenius is from Tunisia approximately 700.000 years ago [3], although it probably originated from Asia where Bos descended from Leptobos [4]. The aurochs was originally a widespread animal. Its range included continental Europe (in Scandinavia only in the south), North Africa including the Nile delta, the Near East except for the Arabian peninsular, India, the south of Siberia and the North of China (1).

Apparently, the range of the aurochs did not include high latitudes (5). Its prime habitat was that of temperate forests and semi-open lands, southwards the range was limited by the savannah and desert, which was not a place for this bovine, and northwards it was limited by the dry steppes (1).

The aurochs had, as cattle do today, the dentition of a grazer (6). Aurochs and cattle probably were very similar in ecology and behaviour as domestication likely did not change food choice and social instincts (1). The diet of aurochs not only included grasses but also twigs and acorns, according to historic sources (1). It is known from contemporaneous reports that the aurochs lived in herds of about 30 animals (1). These herds probably included young animals and cows, while adult bulls lived solitary, much like living wild bovines (1).

The estimated natural range of Bos primigenius. Data was obtained from Phylacine (17). Images are samples of habitats within the range.

Terms of use: The images used are attributed to (From middle to right): Adityamadhav83 and Christian Bolz. Both under a CC BY-SA 4.0. No rights reserved on the left-most image.

Extinction and historic accounts

During the Neolithic (12 to 6.5 kya), the aurochs was still abundant in China (7). In India, it was found until 4200 years ago (8). During the 9th century BC, the aurochs was still found in Mesopotamia, as the Assyrian king Assurnassirpal II reportedly caught aurochs on a hunt (1). Herodotus describes wild bovines living in Libya in the 5th century BC, but it is unclear if those bovines were indeed aurochs or feral cattle (1). In the lack of unambiguous data, it cannot be ascertained when exactly the aurochs disappeared outside Europe, but must be assumed that it disappeared from North Africa and the Near East during the first millennium BC because there are no later records of this animals in historic texts and also no bone findings (1).

In Europe, the aurochs vanished first on the British Isle around 1300 BC (1). In Italy, the bovine was found at least until the first century BC, as suggested by ancient roman texts (1). Aurochs were, among other wild animals, caught and used in arena fights (1). Julius Caesar described the aurochs living in the Hercynian forest of Germania in De bello gallico in the year 53 BC. He writes that aurochs were “little below an elephant in size” and that the Germans used to catch these animals in pits, and used their horns as drinking cups (9). During the first century, the aurochs vanished from the Netherlands and Denmark. In France, it was found until the 9th century. Charles the Great is known to have hunted an aurochs “with huge horns” (1).

When the aurochs vanished from central Germany is uncertain because this bovine became increasingly confused with the wisent (1). When exactly it disappeared from Russia is not known either (1). In East Prussia, it survived in the so-called Great Wilderness, an extensive wilderness area, at least until 1500 (1). A single horn core from Moldavia might suggest its presence in this country until the 16th and 17th century (10). The relict population in Poland is well-documented. The Polish Royal forests were the last living area of the aurochs for which there are written accounts. The last population lived in the forest of Jaktorow. This population was looked after by hunters employed by the crown (1). The numbers of the animals were recorded in reports by those gamekeepers. For the year 1564, 38 aurochs were found. The number of the animals continuously decreased, although the gamekeepers had an eye on the aurochs. During winter, they were given supplementary hay at feeding places (1). Hides and horns were sent to the Polish king. Bulls that had been seen covering domestic cows were shot and given to the farmers (1). In the second half of the 16th century, the Swiss naturalist Anton Schneeberger visited the population in Jaktorow. In his letter to Conrad Gesner, published in 1602, Schneeberger gives a precise description of these aurochs. The report of 1564 mentions that they do not breed well because the local farmers feed their horses and cattle where also the aurochs graze, and consequently they could not thrive (1). In 1599, 24 aurochs were left. In 1620, the last aurochs bull died and its horn was ornamented and is now at the national armoury of Stockholm. Only one cow was left, which died in 1627 (1). The precise records of the last population of Jaktorow make the aurochs the first case of an extinction to be documented by humans (1).

The extinction of the aurochs was caused by man. The expanding human civilization was responsible for a dramatic habitat loss as much of its living areas were turned into pastures for domestic cattle and horses or agricultural fields. During the very end of its existence, the aurochs was pushed into hideaway regions such as deep forests and marshes, until also these areas were turned into pastures for livestock. Also, hunting was a factor. The aurochs was a popular game animal for hunters as it made spectacular trophies. That aurochs were hunted, as already mentioned by Caesar, is evident from numerous drinking horns that are preserved (1). Also, when the aurochs was already very rare, diseases transferred from neighboring cattle were a threat for the decreasing populations (1).

If it had not been for these anthropogenic factors, the aurochs would probably still be a common and widespread animal. It is the largest terrestrial mammal that has been exterminated by man in historic times.

Domestication of the aurochs

The living descendants of the aurochs can be subdivided into two genetic lineages: taurine cattle and zebuine (Asiatic humped) cattle. They are the result of two different domestication events and descend from two different subspecies of aurochs. Taurine cattle were domesticated in the Near East and zebuine cattle in the Indus Valley, Pakistan (11). According to a 2012 study, taurine cattle descend from only about 80 aurochs cows (12).

After domestication, the gene pools of wild aurochs and domestic cattle probably remained connected to some degree. Mitochondrial haplotypes suggest genetic influence from wild populations into the domestic stock in Europe (13,14,15), and the full sequencing of the genome of a British aurochs male from 8000 years ago has shown that British landraces are influenced by local aurochs (13).

Attempts to “breed back” the aurochs

Since the aurochs left living descendants, there have been efforts to “breed back” the wildtype by selective breeding with domestic cattle. The earliest “breeding-back” attempt was done by two German zoo directors named Heinz and Lutz Heck. The result is called Heck cattle, which do resemble the aurochs in colour and sometimes also horn shape, but they are considerably smaller and have the stocky domestic body type (16), which is why there has been the attempt to improve Heck cattle in terms of aurochs-likeness by crossing in primitive Southern European breeds. The result is called Taurus cattle. These cattle resemble the aurochs better than usual Heck cattle as they are considerably larger (the largest bull measured so far reaches 170 cm at the shoulders), have longer legs and snouts and forwards-facing horns. Taurus cattle and Heck cattle are used in conservational grazing projects in several European countries where they live free all year round. There also is the Tauros Programme (not to be confused with Taurus cattle), which also has released crossbreeds of primitive breeds and Highland cattle into grazing projects under the frame of the Rewilding Europe initiative. The youngest “breeding-back” attempt is the Auerrind project in Germany.

Despite a phenotypic resemblance between the aurochs and “breeding-back” cattle, the original wild bovine remains extinct.

Fig. 3: A Taurus bull in the Lippeaue reserve which optically resembles the aurochs. © Daniel Foidl

Citations

1. Van Vuure: Retracing the aurochs: history, morphology and ecology of an extinct wild ox. 2005.

2. Frisch: Der Auerochs – das europäische Rind. 2010

3. Martínez-Navarro, B., Karoui-Yaakoub., N., Oms, O. et al.:The early Middle Pleistocene archeopaleontological site of Wadi Sarrat (Tunisia) and the earliest record of Bos primigenius", Quaternary Science Reviews. 2014.

4. Tong et al.: New fossils of Bos primigenius (Artiodactyla, Mammalia) from Nihewan and Longhua of Hebei, China. 2014.

5. Bunzel-Drüke, Finck, Kämmer, Luick, Reisinger, Riecken, Riedl, Scharf & Zimball: „Wilde Weiden: Praxisleitfaden für Ganzjahresbeweidung in Naturschutz und Landschaftsentwicklung“. 2011

6. Lynch et al.: Where the wild things are: aurochs and cattle in England. 2008.

7. Cai et al.: Ancient DNA reveals evidence of abundant aurochs (Bos primigenius) in Neolithic Northeast China. 2018.

8. Chen et al.: Zebu cattle are an exclusive legacy of South East Asia Neolithic. 2009.

9. Julius Caesar: De bello gallico.

10. Bejenaru et al.: Holocene subfossil records of the aurochs (Bos primigenius) in Romania. 2012.

11. Beja-Pereira et al.: The origin of European cattle. Evidence from modern and ancient DNA. 2006.

12. Bollongino et al.: Modern taurine cattle descended from small number of near-eastern founders. 2012.

13. Park et al.: Genome sequencing of the extinct Eurasian wild aurochs, Bos primigenius, illuminates the phylogeography and evolution of cattle. 2015.

14. Bonfiglio et al.: The enigmatic origin of bovine mtDNA haplogroup R: Sporadic interbreeding or an independent event of Bos primigenius domestication in Italy? 2010.

15. Achilli et al.: Mitochondrial genomes of extinct aurochs survive in domestic cattle. 2008.

16. ABU info 06/07: Bunzel-Drüke, Scharf & Vierhaus: Lydias Ende - eine Tragikomödie.

17. Faurby, S., Pedersen, R. Ø., Davis, M., Schowanek, S. D., Jarvie, S., Antonelli, A., & Svenning, J.C. (2020). PHYLACINE 1.2.1: An update to the Phylogenetic Atlas of Mammal Macroecology. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3690867