The Scimitar Cat (Homotherium)

Fig. 1: Two scimitar cats in pursuit of a young woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). Note: Newer evidence indicates that Homotherium was most likely brown. Painting used with permission by the author Hodari Nundu.

Taxonomy

Homotherium, also known as the scimitar or scimitar-toothed cat, is a genus of sabertoothed cat in the felid subfamily Machairodontinae, the true sabertoothed cats. Machairodontines are the extinct sister group to the living conical-toothed cats, with both subfamilies – Felinae and Machairodontinae – sharing a common ancestor in the early Miocene, about 20 mya (1, 2). Although both were machairodontines, Homotherium was only distantly related to Smilodon, the other, more widely known sabertoothed cat of the late Pleistocene. The genus Homotherium itself evolved during the early Pliocene, most likely in Africa (3). Both its temporal and geographic range are enormous, encompassing much of the Pliocene and the entire Pleistocene, and at times covering the Old World with Africa and Eurasia, even penetrating into the Sunda Islands (at the time connected by land), as well as North America. Its purported existence in South America is based on findings from Venezuela, however, these have been reinterpreted (3, 4) as belonging to Xenosmilus, a different, although closely related genus that we will only briefly touch on here. The taxonomic history of the genus Homotherium is long and complex, and the number of recognised species varies between authors. The latest taxonomic revision by Jiangzuo et al. (2022) recognises the following species, in approximate temporal succession: H. hadarensis, H. problematicus, H. crenatidens, H. crusafonti, H. latidens and H. serum (3). The evolutionary outline below follows their findings.

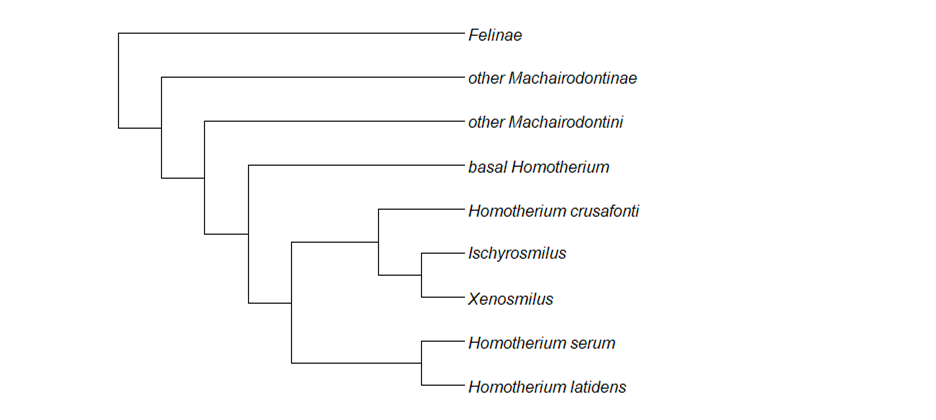

Within the Machairodontinae, Homotherium is grouped among the tribe Machairodontini, along with genera such as Lokotunjailurus, Machairodus itself and Amphimachairodus. The latter is thought to have given rise to the large Adeilosmilus of the African Mio-Pliocene, which in turn is tentatively assumed to be ancestral to Homotherium, via transitional forms. The earliest recognised species of Homotherium itself, H. hadarensis and H. problematicus, date from the African early Pliocene (4mya). H. crenatidens then spread out of Africa, giving rise to two lineages. One of these contains the middle to late Pleistocene H. latidens and the late Pleistocene H. serum. It should be noted here that although Jiangzuo and colleagues recognise both as valid, other researchers have argued that all late Pleistocene Holarctic Homotherium belong to only one species, Homotherium latidens. This is corroborated by a high degree of genetic similarity between specimens from both landmasses (1), while Jiangzuo and colleagues point out morphological differences in size and dentition. The second, New World line of descent from H. crenatidens leads to Xenosmilus, via the transitional forms H. crusafonti and Ischyrosmilus ischyrus. It is apparent, therefore, that Homotherium does not represent a natural relationship group, as it does not comprise all descendants of a most recent common ancestor (Ischyrosmilus and Xenosmilus being nested within Homotherium), but is paraphyletic (Fig. 2). Such taxonomic problems are not uncommon in palaeontology and should not worry us here. They should, however, serve as a warning that the taxonomy of Homotherium is not fully resolved and may change drastically in the future. What is presented here is only one interpretation of its phylogenetic history, and must not be treated as anything else.

Fig. 2: A simplified visualisation of Homotherium's relationship to other cats, drawn after Jiangzuo et al. (2022). Xenosmilus and Ischyrosmilus are nested within Homotherium, making Homotherium paraphyletic. Felinae, the outgroup, are the conical-toothed cats.

Distribution and Age

The earliest scimitar cat finds come from Africa, and its evolution appears to have been in response to a global increase in aridity around the Miocene-Pliocene boundary, leading to a reduction in forest cover and an expansion of open grassland (3). The genus then rapidly expanded out of Africa, and is known from a variety of sites spanning the Pliocene and Pleistocene. By around 1.5mya, the scimitar cat disappeared from its African cradle, and after 400-300kya, it was apparently rare or absent in Eurasia. The only younger remains from the area are a jawbone from the North Sea, dated to ~28-30kya, and a permafrost cub from Yakutia, which is of comparable (~ 35-37kya) age (5). A close mitochondrial relationship between the North Sea specimen and the contemporary H. serum from North America has been noted (1). This may mean that the scimitar cat indeed became extinct in Eurasia in the mid-late Pleistocene, and the American H. serum, with its continuous record throughout the American middle to late Pleistocene, later re-invaded the landmass. Alternatively, the scimitar cat may have been present throughout the Eurasian Pleistocene, but presumably at levels so low as to essentially remain below the “fossil detection rate” (1). In the Americas, Homotherium became extinct in the latest Pleistocene. The early Pleistocene representative of the genus in North America, H. crusafonti, is clearly different in morphology to H. latidens and H. serum, and probably belongs in the New World lineage leading to Xenosmilus. It is thus not discussed hereafter. This New World lineage, interestingly, pursued an opposite evolutionary trajectory to the H. latidens-serum lineage, becoming more robust and bulky in build (3, 6).

Ecology and Morphology

The name Homotherium translates to „same beast”, and yet the scimitar cat was anything but ordinary. Although a true cat, late Pleistocene Homotherium in particular possessed a unique combination of cat-like traits and of traits that are more typically associated with hyenas and dogs. In size, Homotherium broadly overlapped with a modern lion, although considerably larger individuals are known from the late Pliocene and early Pleistocene. For a cat of its size, however, the scimitar cat was strikingly lean. Being lighter in build than a modern lion, it was appreciably leaner than the northern lions (Panthera speleae fossilis, P. s. spelaea, P. atrox) that shared its range (7). Notwithstanding these ostensible constraints, Homotherium was an apex predator of grassland ecosystems throughout its existence. Quite on the contrary, the genus’ evident success is naturally tied to its physical appearance.

Overall, the scimitar cat’s skeleton bears many similarities with other Felidae. Cranially, the most striking difference to conical-toothed cats lies in the elongated and flattened upper canines, a condition that is shared, of course, with other machairodontines. However, in comparison with the so-called dirk-tooths Megantereon and Smilodon that it coexisted with for much of its existence, the scimitar cat’s canines are eponymously stouter, broader and more strongly flattened, featuring a serrated margin, and were most likely covered by the upper lip in life (8, 5). In common with its fellow machairodontines some of the muscle attachment points, called processes, are modified, which allowed for a wider gape to accommodate the long canines, at the cost of a reduced bite force. Other peculiarities of the skull include a pronounced mandibular flange, producing a disproportionate chin, a large nasal cavity, allowing for enhanced oxygen intake, as well as enlarged, forward-facing eye sockets (9, 12, 10).

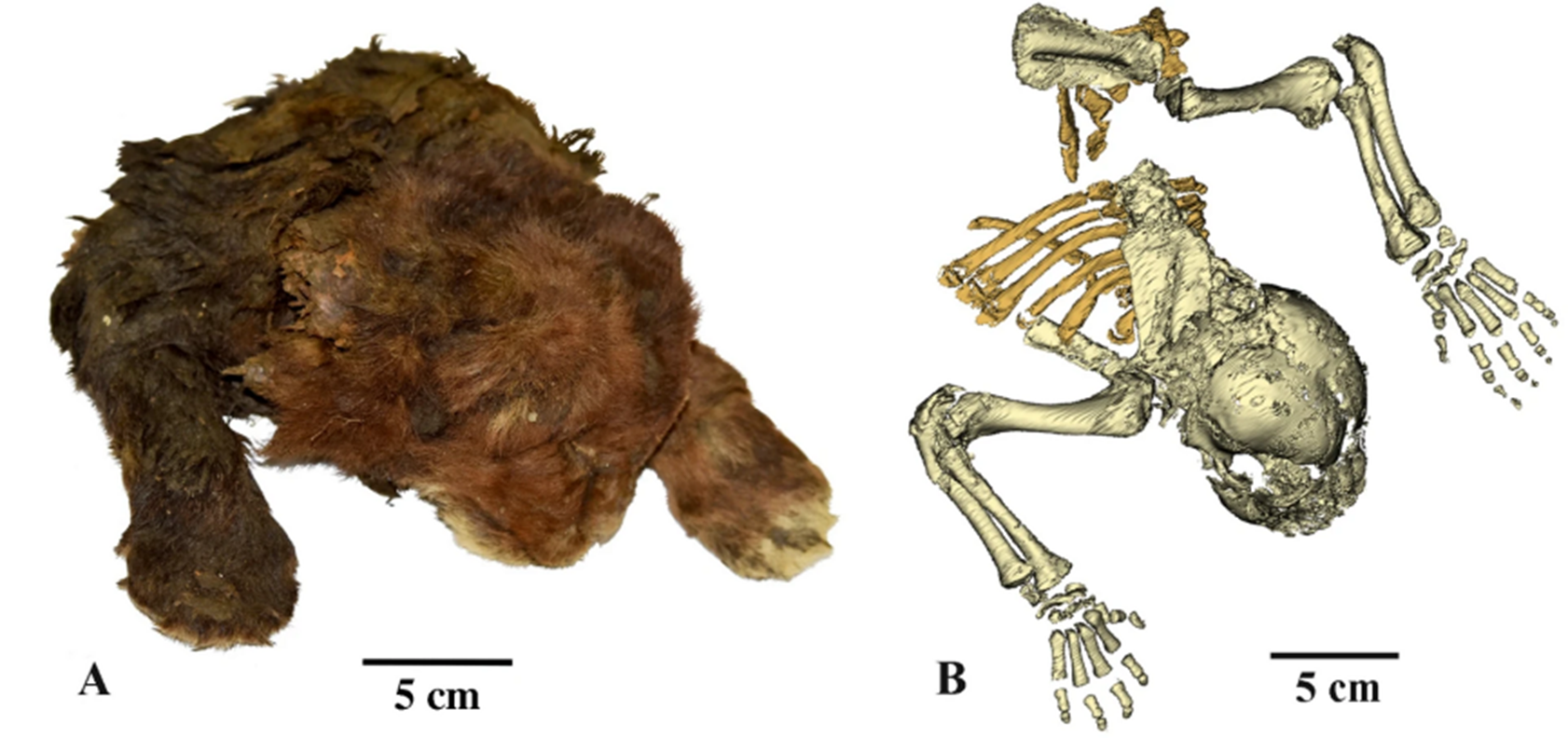

In its postcranium the scimitar cat differs noticeably from other cats, too. In common with other machairodonts, the neck is proportionally longer and stronger, the spine and tail shorter, and the forearms proportionally more robust than in feline cats. In contrast to any other cat, living or extinct, H. serum possessed a sloping, hyena-like backline, as the forelegs were visibly longer than the hindlegs (although the South American machairodont Smilodon populator seems to have convergently adapted a similar condition (9)). Additionally, details in morphology suggest limitations in lateral flexion of the extremities and wrist manoeuvrability, and a partial loss of the ability of claw retraction. The claws were relatively small, except for the dewclaw, which was huge (12). So far, no unequivocal prehistoric depictions of the scimitar cat have been found, and thus reconstructions of its outer appearance had to rely on educated guesses. This changed with the discovery of a cub from the Yakutian permafrost in 2020, described in 2024. At 3 weeks old when it died, the cub is dark brown, with longer hair around the neck and what appears to be a white “beard” on its chin. Additionally, it has stronger forelegs, a larger mouth, larger, round paws lacking a carpal pad, and a longer and a much thicker neck than a lion of similar age (Fig. 3) (5). Having familiarised ourselves with some of the anatomical peculiarities of Homotherium, we now turn to the possible ecological implications.

Figure 3: Photograph of a now-lost figurine from Isturitz Cave, France, that has variably been interpreted as a depiction of either a lion or a scimitar cat. Certain features, such as the angular chin and short tail (which may have broken off, however), may argue for the latter identification. The image is in the public domain, and can be found here.

Taken together, the scimitar cat’s morphology paints a picture of an animal without analogue. Its leg morphology mirrors the condition in dogs (Canidae) and hyenas (Hyaenidae), and is probably an adaptation for efficient, sustained running. Another shared resemblance to hyenas is the sloping backline, which is similarly thought to serve in locomotory efficiency (11). The same applies to the reduced claw retractability, which is also seen in the modern cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), where the claws improve grip on the ground during locomotion. Homotherium seems to have used its upper canines in a different way than dirk-tooths, who are generally thought to have employed their extremely elongated fangs in a shearing bite to the throat, severing the victim’s arteries and windpipe (12). In contrast, the scimitar cat’s jaw morphology supports a killing technique more reminiscent of the clamp-and-hold modern big cats utilise (13). In combination with its leg morphology and protruding arc of incisors, this could speak for a killing technique somewhere halfway between that of cats and dogs or hyenas. The emphasis in Homotherium's morphology on efficiency in movement may have compromised its ability to use the forearms to grab and subdue prey as modern big cats do. Instead, the prominent row of large incisors suggests that these played a greater role in grasping, much like in dogs and hyenas (7). Homotherium’s powerful neck muscles and serrated canines would have finally enabled it to kill in a quick and efficient way by inflicting great damage and blood loss (9).

Several lines of evidence suggest group hunting behaviour. On the one hand, despite a relatively lean build, isotopic and palaeontological evidence demonstrates that the scimitar cat targeted large prey of open habitats, such as horses, bison and yaks (14 - 17). Fossils from Friesenhahn Cave in Texas, USA, even suggest the regular preying on and disarticulation and transport of young prairie mammoths (Mammuthus columbi) (9, 12). These findings are best explained by group action. On the other hand, the scimitar cat experienced a strong positive selection for a number of gene families that have been linked to cognition – a precondition for sociality. Other genes that were selected for are associated with enhanced endurance, involving respiratory and circulatory function, as well as genes for enhanced vision and a diurnal circadian clock (being active at day time) (18). A combination of group hunting and its extreme degree of specialisation probably made the scimitar cat a highly efficient hunter: Its lean and cursorial build would have allowed pursuits at a moderately high speed over long distances, while cooperation would have offset some of the downsides that came with this specialisation, such as the relatively reduced individual strength (7).

The scimitar cat’s extensive range is testament to considerable adaptability and climatic insensitivity. A necessary prerequisite seems to have been grassland, with which it is strongly associated. In the late Pleistocene, the scimitar cat was associated with the mammoth steppe especially, but a scarcity of fossils makes reconstructing its full range difficult. During its more 4 million years long existence, the scimitar cat would have come in contact with a number of potential competitors. For much of the Pleistocene, it was accompanied by the dirk-tooth Megantereon, and their interaction is an intriguing one: although the latter was generally smaller, this is not true for all localities. At Zhoukoudian, China, we find large Megantereon remains of Plio-Pleistocene age in association with comparably small Homotherium individuals, and one Megantereon skull is slightly longer than a Homotherium skull from the same deposit (9). A similar dynamic may have given rise to Smilodon in America, which is generally thought to have descended from Megantereon, and appears to have eventually superseded Homotherium in abundance in the American Pleistocene. Another significant contributor to ending the scimitar cat’s predominance was probably the evolution of lions in the African late Pliocene, and their subsequent expansion across the northern hemisphere (11, 19). In Europe, the appearance of lions coincides with a noticeable decline in Homotherium remains, and there is indication that the lion may have outcompeted the scimitar cat here (11). Other carnivores the scimitar cat would have shared its grassland habitat with include hyenas (Pachycrocuta brevirostris, Chasmaporthetes spp., Crocuta spp.), cheetahs (Acinonyx spp.), dogs (Canis spp., Aenocyon dirus) and ursine and tremarctine bears (Ursus, Arctodus).

Despite this fierce competition, Homotherium evidently remained successful throughout the Pleistocene in North America, in the presence of both lions and Smilodon, which raises the question why it became extinct so much earlier in Africa than in Europe, and earlier in Europe than in America. This may indicate that another competitor may have played a crucial role: the genus Homo. A brain size increase in hominins has been linked to prehistoric large carnivore extinctions in Africa (20), and the scimitar cat’s extinction here coincides with the development of the Acheulean culture, which is associated with Homo erectus. Later, the apparent break point of around 400-300kya, after which the scimitar cat appears to have become very rare in Europe, seems to roughly coincide with a more general and permanent human settlement of Europe above 45°N by Homo heidelbergensis (12). Finally, the scimitar cat’s definitive extinction in America around 12kya coincides with the extinction of most large mammals on the continent, which is strongly correlated with the spread of Homo sapiens (22). None of these correlations implies causation, of course, but the interrelationship between developments in genus Homo and extinction trends in Homotherium does strike as conspicuous.

Figure 4: Homotherium cub in right lateral and dorsal view (A) and skeleton (B). The image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, and the original can be found here.

Figure 5: Homotherium cub in right lateral and dorsal view (A)and skeleton (B). The image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, and the original can be found here.

References

1. Paijmans, J. L. A. et al. Evolutionary History of Saber-Toothed Cats Based on Ancient Mitogenomics. Current Biology 27, 3330-3336.e5 (2017).

2. Werdelin, L., Yamaguchi, N., Johnson, W. & O’Brien, S. J. Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae). in Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids 59–82 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2010).

3. Jiangzuo, Q., Werdelin, L. & Sun, Y. A dwarf sabertooth cat (Felidae: Machairodontinae) from Shanxi, China, and the phylogeny of the sabertooth tribe Machairodontini. Quaternary Science Reviews 284, 107517 (2022).

4. Manzuetti, A., Jones, W., Rinderknecht, A., Ubilla, M. & Perea, D. Body mass of a large-sized Homotheriini (Felidae, Machairodontinae) from the Late Pliocene-Middle Pleistocene in Southern Uruguay: Paleoecological implications. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 149, 105231 (2024).

5. Lopatin, A. V. et al. Mummy of a juvenile sabre-toothed cat Homotherium latidens from the Upper Pleistocene of Siberia. Sci Rep 14, 28016 (2024).

6. Martin, L. D., Babiarz, J. P., Naples, V. L. & Hearst, J. Three Ways To Be a Saber-Toothed Cat. Naturwissenschaften 87, 41–44 (2000).

7. Antón, M. Behaviour of Homotherium in the Light of Modern African Big Cats. in The Homotherium finds from Schöningen 13II-4: Man and Big Cats of the Ice Age (eds. Conard, N. J., Hassmann, H., Hillgruber, K. F., Serangeli, J. & Terberger, T.) 9–23 (Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums, Mainz, 2021).

8. Antón, M. et al. Concealed weapons: A revised reconstruction of the facial anatomy and life appearance of the sabre-toothed cat Homotherium latidens (Felidae, Machairodontinae). Quaternary Science Reviews 89, 107471 (2022)

9. Turner, A. & Antón, M. The Big Cats And Their Fossil Relatives: An Illustrated Guide To Their Evolution And Natural History. (Columbia University Press, New York, 1997).

10. Jiangzuo, Q. et al. Origin of adaptations to open environments and social behaviour in sabretoothed cats from the northeastern border of the Tibetan Plateau. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 290, 20230019 (2023).

11. Anton, M., Galobart, A. & Turner, A. Co-existence of scimitar-toothed cats, lions and hominins in the European Pleistocene. Implications of the post-cranial anatomy of Homotherium latidens (Owen) for comparative palaeoecology. Quaternary Science Reviews 24, 1287 (2005).

12. Antón, M. Sabertooth. (Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2013).

13. Figueirido, B., Lautenschlager, S., Pérez-Ramos, A. & Van Valkenburgh, B. Distinct Predatory Behaviors in Scimitar- and Dirk-Toothed Sabertooth Cats. Current Biology 28, 3260-3266.e3 (2018).

14. Hopley, P. J. et al. Stable isotope analysis of carnivores from the Turkana Basin, Kenya: Evidence for temporally-mixed fossil assemblages. Quaternary International 650, 12–27 (2023).

15. DeSantis, L. R. G., Feranec, R. S., Antón, M. & Lundelius, E. L. Dietary ecology of the scimitar-toothed cat Homotherium serum. Current Biology 31, 2674-2681.e3 (2021).

16. Bocherens, H. Isotopic tracking of large carnivore palaeoecology in the mammoth steppe. Quaternary Science Reviews 117, 42–71 (2015).

17. Fox-Dobbs, K., Leonard, J. A. & Koch, P. L. Pleistocene megafauna from eastern Beringia: Paleoecological and paleoenvironmental interpretations of stable carbon and nitrogen isotope and radiocarbon records. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 261, 30–46 (2008).

18. Barnett, R. et al. Genomic Adaptations and Evolutionary History of the Extinct Scimitar-Toothed Cat, Homotherium latidens. Current Biology 30, 5018-5025.e5 (2020).

19. Yamaguchi, N., Cooper, A., Werdelin, L. & Macdonald, D. W. Evolution of the mane and group-living in the lion (Panthera leo): a review. Journal of Zoology 263, 329–342 (2004).

20. Faurby, S., Silvestro, D., Werdelin, L. & Antonelli, A. Brain expansion in early hominins predicts carnivore extinctions in East Africa. Ecology Letters 23, 537–544 (2020).

21 Svenning, J.-C. et al. The late-Quaternary megafauna extinctions: Patterns, causes, ecological consequences and implications for ecosystem management in the Anthropocene. Cambridge Prisms: Extinction2, e5 (2024