Sardinian Giant Otter - Megalenhydris barbaricina

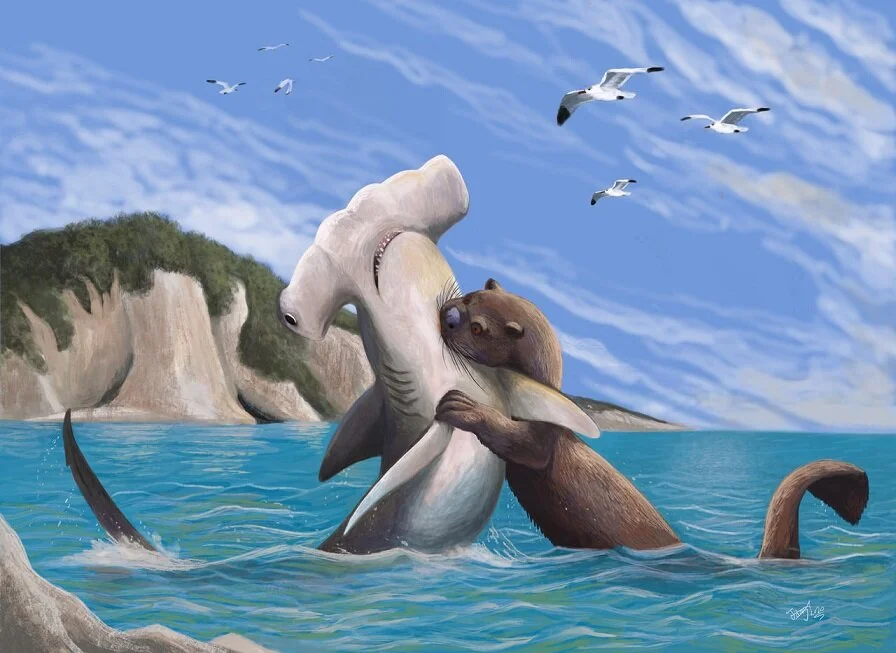

Fig 1. An artist’s interpretation of Megalenhydris barbaricina attacking a hammerhead shark (Sphyrna) Painting used with permission from the artist Hodari Nundu.

Taxonomy

The exact affinities of the giant otter Megalenhydris barbaricina are somewhat difficult to determine, on account of its scanty remains (only a single specimen is known) (1). The taxonomy of otters is somewhat contentious, but a broad division can be made between the Lutrini, to which pertain the otters of genus Lutra, among them the European otter (Lutra lutra), and the Aonychini, to which pertain the clawless otters (Aonyx) (4). When first published, the Sardinian giant otter was suggested to be an aonychoid otter. This was on account both of its seemingly aonychoid dentition and the shape of its talons (1) (3). More recently, however, this placement has been reconsidered, chiefly on the basis of the discovery of the Middle-Pleistocene Corsican species Lutra castiglionis (1). This taxa has a distinctively flattened sacrum, reminiscent of the flattening of the first five vertebrae in M. barbaricina (the sacrum here is not known). It appears, on account of this, that L. castiglionis, or a close relative thereof, is the most likely ancestor of Megalenhydris (1). This would make the Sardinian giant otter a member of the Lutrini-branch.

Distribution

As the species is represented by only one specimen, little can be said about the distribution on the basis of the fossils themselves. The remains were found in the bottom of the Grotta di Ispinigoli, an abyssal cave near the village of Dorgali on the island’s east coast (3). However, the animal being a strong swimmer (2) (1), and the inhabitant of an island, it seems safe to presume that Megalenhydris would have had a distribution across the coasts and waterways of Sardinia, and perhaps its offshore islands. It may well have been rare in the interior, however, on account of its strong aquatic adaptations.

Fig 2. The probable range of Megalenhydris barbaricina. Images used by Giancarlo Dessì and cisko66, both licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported. Images are unedited.

Morphology and ecology

The Sardinian giant otter would have been an imposing animal in life. Purely on the basis of its first molar, a body-mass would be predicted of around 17 kg, but once the remainder of the skeleton is taken into account, this estimate rises drastically (2). Evidently, M. barbaricina was far larger than the extant giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis), which at 28 kg is already a sizeable animal. It does not seem unreasonable to guess that Megalenhydris may been as heavy or heavier than a grey wolf (Canis lupus), in which case it would be well-and-away the largest predator on Sardinia (5) (6).

The Sardinian giant otter had strong aquatic adaptations—possibly stronger than in any other otter. Its tail was highly dorsoventrally flattened, its claws seemingly adapted for catching bottom-dwelling fish and crustaceans (1) (2). The reasons for the animal’s extreme adaptations, including the abnormal size, may perhaps relate to it sharing its island habitat with not one but two other endemic otters. (1). One, Sardolutra ichnusae, was a small, marine species, specialised in hunting fast fish. The other, Algarolutra majori, hunted also crustaceans. In such a context, which can only be described as a community of otters on Sardinia, it is not surprising that rather radical niche-partitioning would take place. Alongside this diversity of otters lived a host of other peculiar and unique species. Pleistocene Sardinia was marked by high degrees of endemism (6) (7), its fauna including dwarf deer (Praemegaceros cazioti), pygmy elephants (Mammuthus lamarmorai), diminutive wild dogs (Cynotherium sardous) and an endemic pika (Prolagus sardus), the latter of which survived into historical times.

The ultimate extinction of the Sardinian giant otter is wrapped in mystery. Due to being covered in calcite, we cannot even directly date the one specimen we have, though contextual evidence indicates a Late Pleistocene or Holocene provenance (3). What this general timeframe does allow us to say with reasonable certainty, is that the fate of Megalenhydris was likely tied up to that of the broader Sardinian fauna. Here, our picture is somewhat clearer. Importantly, there is no evidence for a faunal turnover either during the Late Pleistocene or at the Holocene boundary (7). The earliest undisputed evidence for human settlement on the island is from 9.0–8.5 kya, though controversial earlier dates have been proposed. The weight of the evidence indicates an initial settlement some ways into the Holocene, possibly temporary at first but certainly permanent by the time of the Neolithic. Though this heavily implicates early humans as the chief cause of the extinctions, it is at present not possible to say whether the bulk of extinctions occurred at the time of first arrival or with the coming of agriculture (7) (6).

Fig 3. Skeletal of Megalenhydris barbaricina. The areas in white are preserved and the areas in grey speculative. More material exists for M. barbaricina but remains unpublished. Skeletal by August Helmke, used with permission.

Citations

1. Willemsen, G. (2006). Megalenhydris and its relationship to Lutra Reconsidered. Hellenic Journal of Geosciences. 41: 83-87.

2. Lyras, G., Van Der Geer, A. and Rook, L. (2010). Body size of insular carnivores: evidence from the fossil record. Journal of Biogeography. 37(6). 1007-1021. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02312.x

3. G. F. Willemsen & A. Malatesta (1987). Megalenhydris barbaricina sp. nov., a new otter from Sardinia. Proceedings of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, B. 90: 83–92.

4. Hussain, S. A., Gupta, S. K., de Silva, P. K. (2011). Biology and Ecology of Asian Small-Clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus (Illiger, 1815): A Review. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 28 (2): 63 - 75

5. Lyras, G. A. & van der Geer, A. A. (2006). Adaptations of the Pleistocene island canid Cynotherium sardous (Sardinia, Italy) for hunting small prey. Cranium 23 (1). 51-60

6. Palombo, M. R. (2009). Biochronology, paleobiogeography and faunal turnover in western Mediterranean Cenozoic mammals. Integrative Zoology. 4. 367-386. DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-4877.2009.00174.x

7. Palombo, M., Antonioli, F., Lo Presti, V., Mannino, M., Melis, R., Orru, P., Stocchi, P., Talamo, S., Quarta, G., Calcagnile, L., Deiana, G. and Altamura, S. (2017). The late Pleistocene to Holocene palaeogeographic evolution of the Porto Conte area: Clues for a better understanding of human colonization of Sardinia and faunal dynamics during the last 30 ka. Quaternary International. 439. 117-140. DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2016.06.014