Tapirus veroensis

Taxonomy

Tapirus veroensis is a species of tapir first described in 1918 by Florida State geologist F. H. Sellard (1). The first specimen was collected in 1915 in Vero Beach, Florida, the locale from which its specific epithet is derived (1). Since 2010, it has been placed in the subgenus Helicotapirus with its closest relatives, Tapirus haysii (sometimes referred to as T. copei) and T. lundeliusi (2). These species occupied a similar range to T. veroensis but existed slightly earlier, becoming extinct in the late Blancan and early Irvingtonian respectively (2).

When first described, subgenus Helicotapirus was suggested to belong to one of two lineages of Tapirus, also containing Miocene-Pliocene species Tapirus polkensis, and two extant species; Tapirus bairdii and Tapirus indicus (the other clade being made up of T. terrestris and T. pinchaque) (2, 3). However, it may be worth noting that another hypothesis exists concerning the relationships of living tapirs, placing all American tapirs in a clade to the exclusion of the Asian T. indicus (4).

T. veroensis was contemporaneous with two other North American tapir species, Tapirus californicus and T. merriami, but the phylogenetic affinities of these species are yet to be determined with confidence, though it has been suggested that they likely share a fairly close relationship with T. veroensis and the other members of Helicotapirus (2).

Distribution and Age

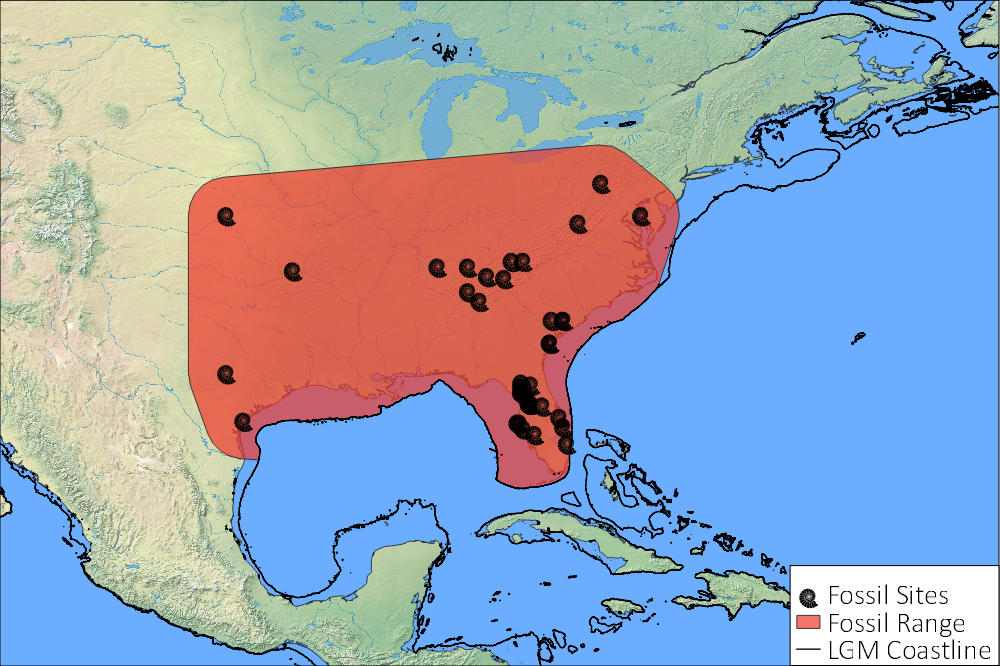

Apart from the type locality of Vero Beach, Florida, remains of this species have been recovered from a variety of other sites across the state (5). Moreover, T. veroensis appears to have had a broad distribution across what would become the southeastern United States, with remains being found in Georgia, Tennessee, Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania (5). The extent of the range of T. veroensis has been the subject of some discussion, as its occurrence at inland locales in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Texas during glacial periods suggest a degree of cold tolerance not known in most extant congeners (6).

That being said, it seems to have had shared its relatives’ predilection towards forested habitat, especially those containing or adjacent-to bodies of water (2). Known fossils seem to suggest a distribution across temperate (and subtropical in the case of coastal Florida) forests in the southeastern United States, skirting the spruce and fir taiga that dominated the mid-to-high elevations of the eastern US during glaciated periods. The species seems to have occurred from the coastal plain and Piedmont of Maryland and Pennsylvania south along the coast to Texas, wrapping around the Appalachians into the interior lowlands of Tennessee and possibly beyond (5). The absence of T. veroensis further west is perhaps explained by the presence of other species (Tapirus merriami and T. californicus), with competitive exclusion preventing co-occurrence of multiple species.

The earliest definitive records of Tapirus veroensis are dated to the late Irvingtonian, 300kya (5). However, a Florida specimen from the middle Irvingtonian previously thought to be a late-surviving Tapirus haysii has instead been suggested to represent the earliest known specimen of Tapirus veroensis (2). The extinction of T. veroensis appears to have occurred around 11,000 years ago near the Pleistocene-Holocene boundary, coinciding with the extinction of a majority of North American megafauna (5).

Fig 1. The estimated palaeorange of Tapirus veroensis, based on fossil sites (11).

Morphology and Ecology

Morphologically, Tapirus veroensis is very similar to extant tapirs, with a retracted nasal bone indicative of a fleshy trunk, a brachyodont (short-crowned) dentition suited for browsing, and a long yet robust, barrel-shaped torso on relatively-short legs (7). It has been described as being similar to the extant T. terrestris in size (2). Along with other members of Helicotapirus, T. veroensis is distinguished from other tapirids primarily by cranial characters, such as spaces between the teeth and a spiral-shaped depression on the nasal and frontal bones (from which the name of the subgenus – Helicotapirus – was derived) (7).

T. veroensis is strikingly similar to other species within its subgenus. It is almost identical to T. lundeliusi (apart from subtle cranial differences) but is slightly larger on average and occurs later (2). Comparison with T. haysii likewise yields a great degree of similitude, with slight cranial differences, a disparity in body size (T. haysii is significantly larger), and temporal separation (T. haysii occurs earlier) (2).

In terms of ecology, Tapirus veroensis was likely largely similar to living tapirs, solitary denizens of forested habitats near bodies of water, as its remains have been found in locales that seem to reflect this type of palaeoenvironment (1). However, its co-occurrence with temperate/boreal species such as the reindeer Rangifer tarandus and the muskox Bootherium bombifrons at sites in Virginia and Texas suggest some sort of adaptation towards surviving sub-freezing temperatures, something today restricted to the mountain tapir (Tapirus pinchaque) (6, 8). This species, also called the woolly tapir, possesses a long, thick coat, which aids in its survival in high Andean paramo, and similar adaptations have been suggested to have independently evolved in T. veroensis (6).

Extant tapirids are primarily folivorous but also exhibit frugivory and granivory, and are thus important seed dispersers of various plant species. A similar relationship between Nearctic plants and Tapirus veroensis is plausible (1).

Modern tapir species are preyed upon by felids, ursids, and large crocodilians, and given the rogue’s gallery of megafaunal predator species in Pleistocene North America, T. veroensis was almost certainly a common prey item itself. Potential predators of this species up until its extinction in the Holocene include wolves (Canis rufus, Aenocyon dirus), large cats (Puma concolor, Panthera onca, Panthera atrox, Smilodon fatalis), bears (Ursus americanus, Tremarctos floridanus, Arctodus simus, Arctodus pristinus), and crocodilians (Crocodylus acutus, Alligator mississippiensis). Various T. veroensis fossil sites, including the type locality at Vero Beach, have also preserved human remains, and it is likely this species was a food source for contemporaneous hunters (1, 9).

The common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) is known to feed prolifically on tapirs and previously occurred in what is now the United States in prehistoric times, so it is likely that T. veroensis was a frequent host (10). It has even been suggested that this species’ extinction was a significant factor in the disappearance of D. rotundus from the region (1). Perhaps the same could be true for the larger, now-extinct vampire species Desmodus stocki of Florida.

References

1. Gelbart, M. (2016, July 6). The extinct Vero Tapir (tapirus veroensis). GeorgiaBeforePeople. Retrieved September 12, 2021, from https://markgelbart.wordpress.com/2011/12/20/the-extinct-vero-tapir-tapirus-veroensis/.

2. Hulbert, Richard. (2010). A new early Pleistocene tapir (Mammalia: Perissodactyla) from Florida, with a review of Blancan tapirs from the state. 49. 67-126.

3. Hulbert, Richard & Wallace, Steven. (2005). PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF LATE CENOZOIC TAPIRUS (MAMMALIA, PERISSODACTYLA). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25. 72A-72A.

4. Ruiz-García, Manuel & Vasquez, Calixto & Pinedo, Myreya & Sandoval, S. & Kaston, & Thoisy, B. & Shostell, Joseph. (2012). Phylogeography of the mountain tapir (Tapirus pinchaque) and the Central American tapir (Tapirus bairdii) and the molecular origins of the three South-American tapirs.

5. Tapirus (Helicotapirus) veroensis. Fossilworks. (n.d.). Retrieved September 12, 2021, from http://fossilworks.org/bridge.pl?a=taxonInfo&taxon_no=52070.

6. Graham, Russell & Grady, Frederick & Ryan, Timothy. (2018). Juvenile Pleistocene tapir skull from Russells Reserve Cave, Bath County, Virginia: Implications for cold climate adaptations. Quaternary International. 530-531. 10.1016/j.quaint.2018.06.021.

7. Hulbert, R. C. (2009). Tapirus haysii. Florida Museum. Retrieved September 12, 2021, from https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/florida-vertebrate-fossils/species/tapirus-haysii/.

8. Winkler, Dale & Winkler, Alisa. (2020). New records of late Pleistocene ungulates (Bootherium and Tapirus) from north central Texas. 12. 330-341.

9. Eshelman, Ralph & Lowery, Darrin & Grady, Frederick & Wagner, Dan & McDonald, H.. (2018). Late Pleistocene (Rancholabrean) Mammalian Assemblage from Paw Paw Cove, Tilghman Island, Maryland. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology. 2-15. 10.5479/si.1943-6688.102.

10. Carter, Gerald G. and Wilkinson, Gerald S. (2013). Food sharing in vampire bats: reciprocal help predicts donations more than relatedness or harassment. Proc. R. Soc. B.2802012257320122573. http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2573

11. Palaeobiology Database. (2021). Tapirus veroensis. https://paleobiodb.org