Xenorhinotherium bahiense

Fig 1. A group of Xenorhinotherium, including a juvenile with a Notiomastodon in the background. Artwork by Gabriel Ugueto and used with permission of the artist.

Taxonomy

Xenorhinotherium is a monospecific (11) genus of Macraucheniidae, which also includes the late Pleistocene Macrauchenia patachonica (7), which alongside the middle Pleistocene Macrauchenopsis ensenadensis constitutes the closest known relative (7). The genus literally translates to ‘Strange-nosed beast’ and the species bahiense is named after the brazilian state of Bahia where it has been found (11). Disagreements exist over the validity of the species X. bahiense, with a few authors considering it synonymous with Macrauchenia patachonica (8). In any case Xenorhinotherium bahiense is the taxonomic designation most used in literature.

The Macraucheniids are part of the extinct order Litoptera, native to South America. The order also contains the Proterotheriids such as the Late Pleistocene Neolicaphrium recens (11). The phylogenetic position of Litoptera is uncertain, they are usually considered a sister group to the odd-toed ungulates (Perissodactyla) (3) or the African mammals (Afrotheria) (1), but not especially closely related to any modern-day group.

Distribution and Age

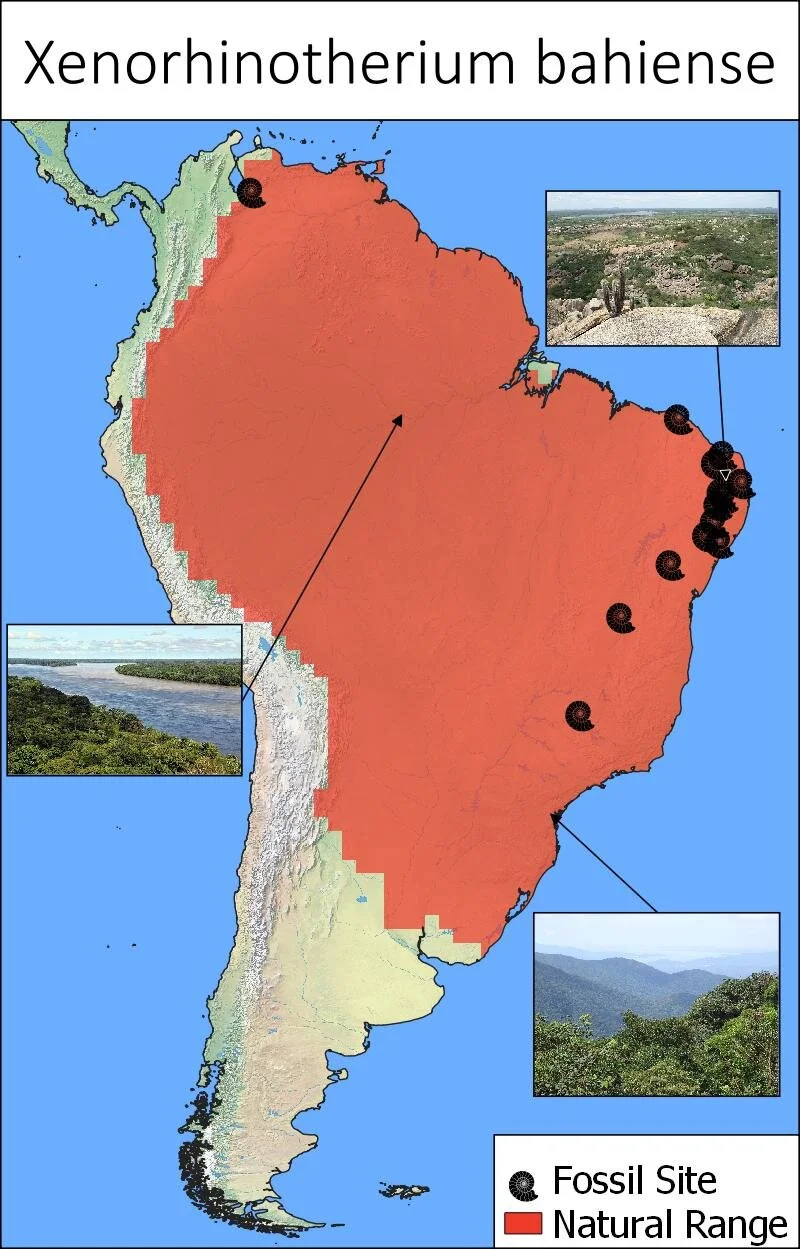

Xenorhinotherium bahiense is known primarily from the East Brazillian tip, as well as a few sites further to the South. A single site in Northern Venezuela has also yielded fossils, indicating an extensive range in the North of the continent (6). One modelling of the species range would also indicate that the Ecuadorian west slopes were highly suitable, and that both Colombia and parts of Peru would yield potentially good habitat. No fossil material is yet known from these locations but are also not especially well studied (6), however cave paintings from southern Colombia may portray Xenorhinotherium (10).

Fig 2. Fossil sites of Xenorhinotherium bahiense and the estimated natural range based on Phylacine modelling (12). Images are samples of nature areas within the natural range.

Terms of use: The images used are attributed to (From top image to bottom): Ivandro batista de queiroz, Neil Palmer and Deyvid Setti and Eloy Olindo Setti. Under a CC BY-SA 3.0, 3.0 and 2.0

Morphology and Ecology

Xenorhinotherium bahiense was a large species at an estimated 940kg (12), though undoubtedly a herbivore there is much controversial abouts it exact diet. Enamel microscars suggest that it integrated a considerable amount of grasses in their diet (Oliviera et al 2020), indicating that the species was a grazer (6). However, the structure of the teeth does not appear conducive to mechanical breakdown of rough vegetation which would not support a grazing role(4), this is particularly notable in the hypsodonty (height of the teeth) which is high in grazers but only of intermediate length when compared to ungulates (9). Oliviera et al 2020 suggests that the lack of dental adaptations could simply be evidence of primary breakdown of grasses in the stomach, as seen in some even-toed ungulates (6).

The carbon-13 concentrations in the teeth of Xenorhinotherium are similar to those of their relative Macrauchenia, both integrate a substantial amount of C3 plants into their diet. Unlike in Macrauchenia the large presence of C3 grasses has not been proven in the diet of Xenorhinotherium, therefore it remains unclear if this species was a primary grazer in arid grasslands or a browser, or somewhat of an intermediate (6). The dietary differences between the two may be expected due to the difference in the shape of the premaxila (front upper jaw), Xenorhinotherium showing a much sharper structure which may be an aid in browsing (9).

The climatic niche of Xenorhinotherium appears to have been tropical, with most fossils found in the intertropical region of Brazil. The habitats of Xenorhinotherium appear to have shifted significantly during their temporal range, both dry and wet periods are inferred from the pollen records of the region and the habitats would variously consist of arid shrubland, savannah and dry and Atlantic forest (6, 9).

Aside from potential dietary differences and habitat preferences, there’s no significant known differences between the ecology of Xenorhinotherium and the better studied Macrauchenia. It was probably a competent runner and may have lived in small groups. It had a proboscis or prorhisces as depicted in putative pictographs made by early South American settlers (10).

Other large herbivores known from the region include the gomphothere Notiomastodon platensis, the giant ground sloths Eremotherium laurillardi, Valgipes bucklandi, Catonyx cuvieri, Nothrotherium maquinense, the giant armadillos Glyptotherium, Panochtus, Holmesina paulacoutoi and Pachyarmatherium brasiliense, the equids Equus ferus and Hippidion principale as well as the Notoungulate Toxodon plantensis and camelid Palaeolama major (5). The principle predators from the region are Arctotherium wingei, Protocyon troglodytes and Smilodon populator (5). The latter of these is known to feed heavily on the close relative Macrauchenia in the pampas (2) which is similar in size to Xenorhinotherium and so may also be the primary predator of Xenorhinotherium, this is corroborated by similar C-13 values in Smilodon and Xenorhinotherium (Oliveira et al 2020, Dantas et al 2021).

Citations

1. Avilla, L.S. & Mothé, D.. (2021). Out of Africa: A New Afrotheria Lineage Rises From Extinct South American Mammals. Frontiers in ecology and evolution 9.

2. Bocherens, H., Cotte, M., Bonini, R., Scian, D., Straccia, P., Soibelzon, L. & Prevosti, F.J.. (2016). Paleobiology of sabretooth cat Smilodon populator in the Pampean Region (Buenos Aires Province, Argentina) around the Last Glacial Maximum: Insights from carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes in bone collagen. Palaeogeography, palaeoclimatology, palaeoecology 449, 463-474.

3. Chimento, N.R. & Agnolin, F.L.. (2020). Phylogenetic tree of Litopterna and Perissodactyla indicates a complex early history of hoofed mammals. Scientific reports 10 (1),13280.

4. Dantas, M.A.T., Lobo, L.S. & Bernardes, C.. (2020). Comments on "fantastic beasts and what they ate: Revealing feeding habits and ecological niche of late Quaternary Macraucheniidae from South America” by K. de oliveira, T. Araújo, A. Rotti, D. Mothé, F. Rivals, L.S. Avilla quaternary science reviews 231 (2020) 106178. Quaternary science reviews 250.

5. Dantas, M. A. T., Bernardes, C., Asevedo, L., Pansani, T. R., Franca, L. D. M., De Aragao, W. S., Santas, F. D. S., Cravo, E., Ximenes, C.. (2021). Isotopic palaeoecology (δ13C) of three faunivores from Late Pleistocene of the Brazilian intertropical region. Historical biology.

6. de Oliveira, K., Araújo, T., Rotti, A., Mothé, D., Rivals, F. & Avilla, L.S.. (2020). Fantastic beasts and what they ate: Revealing feeding habits and ecological niche of late Quaternary Macraucheniidae from South America, Quaternary science reviews 231, 106178.

7. Forasiepi, A.M. & MacPhee, R.D.E. (2016). Exceptional skull of Huayqueriana (Mammalia, Litopterna, Macraucheniidae) from the late Miocene of Argentina, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY.

8. Guerin, C., Faure, M.. (2004). Macrauchenia patachonica Owen (Mammalia, Litopterna) from the São Raimundo Nonato Archaeological Area (Piauí, North Eastern Brazil) and the diversity of the Pleistocene Macraucheniidae. Geobios 37(4), 516-535.

9. Lobo, L. S., Lessa, G., Cartelle, C., Romano, P. S. R.. (2017). Dental eruption sequence and hypsodonty index of a Pleistocene macraucheniid from the Brazilian Intertropical Region. Journal of Palaeontology 91(5), 1083-1090.

10. Morcote-Ríos, G., Aceituno, F.J., Iriarte, J., Robinson, M. & Chaparro-Cárdenas, J.L.. (2021). Colonisation and early peopling of the Colombian Amazon during the Late Pleistocene and the Early Holocene: New evidence from La Serranía La Lindosa. Quaternary international 578, 5-19.

11. Scherer, C., Pitana, V. & Ribeiro, A.M.. (2009). Proterotheriidae and Macraucheniidae (Litopterna, Mammalia) from the Pleistocene of Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil. Revista brasileira de paleontologia 12 (3), 231-246.

12. Faurby, S., Pedersen, R. Ø., Davis, M., Schowanek, S. D., Jarvie, S., Antonelli, A., & Svenning, J.C. (2020). PHYLACINE 1.2.1: An update to the Phylogenetic Atlas of Mammal Macroecology. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3690867