Isles of the Tasman Sea – Part II: Norfolk Island

Introduction

Norfolk Island offers an interesting juxtaposition to Lord Howe Island (Which we looked at in Part 1), as it contains a very similar faunal guild, but the extent and circumstances of its extinctions are somewhat different. The Norfolk Island group is comprised of three isles: Norfolk Island, Phillip Island and Nepean Island, though these latter two are very small. Norfolk Island itself extends 34.6 km2 making it more than twice the size of Lord Howe and somewhat flatter with the highest point reaching 319m above sea level (2). The isolation of the Norfolk Island group is impressive, with the nearest landmasses being New Caledonia (675km N), New Zealand (772km SE), Lord Howe (900km SW), Australia (1367km W) and Fiji (1635km NE) (12). The fossil record of Norfolk Island is somewhat limited with the best remains being known from the Holocene found in conjunction with human settlements, though with a scant record in the Late Pleistocene as well (12). Fortunately, the records of bird sightings by naturalists in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries are much more complete and offers a more resolved timeline for recent natural history.

Fig 1. Map of the Norfolk Island Group

Terms of Use: Own Work

The Faunal Overview

Norfolk Island’s position as a distant waypoint between landmasses has led to a range of endemic species and subspecies with affinities to different neighbors (12). Seven endemic avifauna taxa are known to have gone extinct on the island in historic times: The Norfolk Island Ground Dove (Pampusana nofolciensis), a local species of the New Zealand Pigeon (Hemiphaga novaseelandiae spadicea), the only extinct sub-species of Long-tailed triller (Lalage leucopyga leucopyga), the Norfolk Island Kaka (Nestor productus), White-chested White Eye (Zosterops albogularis) though this species is only listed as critically endangered by the IUCN redlist but considered extinct by the Australian government (3), Norfolk thrush (Turdus poliocephalus poliocephalus) and lastly the second subspecies of the Tasman Starling (Aplonis fusca fusca) (Anderston & White 2001a).

Interestingly, most of the species closely related to those on Lord Howe are still extant. These include the Norfolk parakeet (Cyanoramphus cookie), Long-billed White-eye (Zosterops tenuirostris), Norfolk Gerygone (Gerygone modesta) and local subspecies of New Zealand Fantail (Rhipidura fuliginosa pelzelni) and Golden Whistler (Pachycephala pectoralis xanthoprota (Anderston & White 2001a). The Norfolk boobook (Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata) also survived (Anderston & White 2001a), though the current population is hybridized with the New Zealand boobook (N. n. novaseelandiae) (4). Other endemic avifauna include the Scarlet Robin (Petroica multicolor multicolor) and the local subspecies of Sacred Kingfisher (Halcyon sancta norfolkiensis). The buff-banded rail (Hypotaenidia philippensis), Spotless crake (Zapornia tabuensis) and long-tailed cuckoo (Eydynamys taitensis) are also native to the island (5).

A few bird species are known exclusively from the fossil record and are still not formally named (5). These include a large – potentially flightless - species of rail, ascribed to the genus Gallirallus (This genus has since been split into Gallirallus and Hypotaenidia) (5). It is certainly worth considering if this could be a relative of the Lord Howe Woodhen (Hypotaenidia sylvestris) given the similar fauna of the two islands, but without more material this is unclear. Likewise, a species of swamphen of the genus of Porphyrio is found in the fossil record. It could belong to the purple swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio) though it was not recorded on the island until 1888 (5, 12). Alternatively, the purple swamphen could be a recent arrival as on Lord Howe following the extinction of an endemic swamphen. Fossils of a southern snipe (Coenocorypha sp.) also seems to constitute a new species exclusive to Norfolk Island (5).

The Providence Petrel, (Pterodroma solandri), Pycroft’s Petrel (Pterodroma Pycrofti) and Kermadec Petrel (Pterodroma neglecta) have all become locally extirpated (2, 5). White-faced Storm Petrel (Pterodroma marina) and Black-winged petrel (Pterodroma nigripennis) may also have gone extinct on the island, though their presence prior to European arrival is yet to be corroborated (2, 5) The Kermadec Storm Petrel (Pelagodroma albiclunis) is known solely from fossil deposits on Norfolk Island (2, 5). Some of these species have subsequently begun recolonizing the island from the vicinity (5).

Two species of bat comprise the only mammals: the East-coast free-tailed bat (Micronomus norfolkensis) and Gould’s wattled bat (Chalinolobus gouldii) are known from Norfolk Island but are also present on the Australian mainland (2). Though marine mammals are outside the scope of this article, it should be noted that fossil evidence of a Southern Elephant Seal (Mirounga leonina) has been found on Norfolk Island and constitutes by far the northernmost occurrence of the species in the Pacific (16).

One of the best examples of affinities between Norfolk Island and Lord Howe Island is the presence of the Lord Howe Southern Gecko (Christinus guentheri) and the Lord Howe Skink (Leiolopsima lichenigerum) as the only native reptiles of Norfolk Island, though the former is extinct on the main island and only present on Phillip & Nepean Island (12).

Fig 2. The Norfolk Parakeet (Cyanoramphus cookie), one of the surviving endemic birds of Norfolk Island. It is listed as Endangered on the IUCN Redlist.

Terms of use: This image is licensed under an Attribution 2.0 Generic. It is attributed to David Cook. The image is unedited and can be found here.

The First Wave

One key feature distinguishing Norfolk Island from Lord Howe is the clear evidence of settling by Polynesians. Multiple lines of evidence suggest this, firstly there is the presence of several Polynesian crops including Sow Thistle (Sonchus oleraceus), Maori Celery (Apium prostratum) and Banana (Musa paradisica) (2). Mackphail et al 2001 affirmed that some of these plant species were absent in pollen records extending to the mid-Holocene, though Sow Thistle was present (6). More clear evidence of settlement is found via stone tools from the interior of the island including Adzes – A hand tool reminiscent of an axe or pick, which was used widely by Polynesians (2). Posts and postholes from a probable house have also been found on the island in association with earth ovens and several tools (14). Objects of Melanesian origin are also known from Norfolk Island, including the presence of shells associated with the region and a blade fashioned in Melanesian design (5). Whether these constitute a separate prehistoric arrival or are the product of 19th century Melanesian settlers on the island is an open question (2). Dating of charcoal remains present at archaeological sites have indicated that the settlement occurred around 1200AD and persisted a century or two (1). A few remains also date to more recently than 1500AD, it is unclear if they constitute natural charcoal or evidence of later settlement (1). Carbon ages of bone material does raise some interesting anomalies, bone remains of a human – possibly Polynesian in origin - are dated to 1470-1630AD, predating the European arrival but indicating late settlement (1). Remains of the Polynesian rats reportedly stretch back as far as 700AD and seashells push the date back to 500AD (1). These latter two dates are however dubious as both seashell carbon dating and that of the Polynesian rat have been demonstrated to show dating biases elsewhere (1). Thus, a reasonable arrival time of around 1200AD might be suggested, this also complements similar arrival times in New Zealand and the Kermadec Islands (2). Furthermore, the presence of several canoe wrecks on the island at European arrival may suggest occasional visits to the island prior to European arrival but during the 18th century, though these could also have drifted to the island (2).

Three primary agents of extinction should be considered in the context of Norfolk Island, both during the initial Polynesian settlement and later European arrivals: Exploitation, Land use changes and invasive species. Extinctions following Polynesian settlement are recorded via their representation in archaeological and natural fossil deposits dating to prior to European arrival. The first and most obvious potential source of extinction is through direct exploitation. Evidence suggests that by far the most consumed bird species on Norfolk Island by Polynesians were petrels and shearwaters, though poor taxonomic resolution doesn’t allow any species to be distinguished barring the small Pycroft’s Petrel. This species becomes rare prior to European arrival, likely because of hunting (5) though the species is also small enough for predation by Polynesian Rats (5) and this likely kept the species rare even after a Polynesian exodus. The larger Kermadec Petrel is also rare in deposits from the early European settlements, indicating that Polynesian pressure also took its toll on that population (5).

The Polynesian rat (Rattus exulans) is also known from an abundance of sub-fossil remains, and this species is a common commensal of Polynesian settlements (2). The genetics of rats on Norfolk Island indicate an affinity to New Zealand, indicating that Norfolk Island was colonized from the East (8, 9), both locations have haplogroups from East Polynesia and Melanesia (9). The fossil snipe is known solely from natural deposits; thus, it doesn’t appear to have been frequented as a prey by the Polynesian settlers. Its extinction can then likely be attributed to the arrival of the Polynesian rat which has been linked to the extinction of snipes elsewhere (5). The extinction of the Lord Howe Southern Gecko has also been suggested to result from this invasion, as there is no mention of the taxon by British settlers and it survives on nearby Phillip and Nepean Island, as well as Lord Howe, islands which all lack Polynesian rats (12)

Land use changes in the wake of Polynesian settlement appear to have been relatively minor. Clearings, which were likely created by the Polynesians are identified by later European settlers, however these are few and the island was almost entirely covered in forest by the 18th century (15). As mentioned earlier, there is clear evidence of cultivation on the island, rows of banana trees are reported along freshwater streams nevertheless agriculture does not appear to have dominated the landscape (6, 15).

Fig 3. A Polynesian Rat (Rattus exulans), a common commensal of the Polynesian people which is nearly ubiquitous in the South-West Pacific.

Terms of use: This image is licensed under an Attribution 2.0 Generic. It is attributed to Forest and Kim Starr. The image is unedited and can be found here.

The Second Wave

The Island was discovered by the HMS Resolution in 1774 under the command of the famous explorer James Cook, reporting the island devoid of humans (2). Whatever the impact and longevity of the Polynesian occupation it does not seem to have developed a fear of predators in the local avifauna as birds were reportedly tame when Europeans arrived (2) and this had a huge impact on the aftermath of settlement. In 1788 the European settlers established the first permanent habitation on the island since the Polynesians disappeared (2, 10), though this was initially limited to only a few dozen people (10). More settlers arrived in the subsequent years.

The local extinction of the providence petrel can be partially attributed to hunting by these early Europeans sailors and settlers. This pressure was profound – estimates vary but at least 200,000 and perhaps as many as 435,000 Providence Petrels were harvested each year between 1790 and 1793 (2, 5, 10), however the bird ceased as a meaningful food source in 1795 as supplies and agricultural developments rendered it unnecessary. The species was purportedly still plentiful at this time (10). Therefore, supplementary explanations must be examined which to justify the extinction, though the population was likely much diminished by 1795 (10). How long the Providence Petrel held on, is unclear as records of them cease after this time (5), likely they were extinct before the British recolonization in 1825 (10), though unsubstantiated report from Phillip Island may indicate a survival there until 1900 (13). The extinction of the Providence Petrel on Phillip Island - where exploitation seems to have been much lower - would seem to indicate that invasive species were the driving factor of decline there. Pigs, goats and rabbits are all known from Island, but notably not rats (13) and all three species have since been removed from Phillip Island, and Providence Petrels have returned (13). Perhaps similar forces from invasives can explain the extinction on the mainland? The extinction date of Pycroft’s Petrel and Kermadec Petrel is unclear as they are known only from sub-fossil remains, so whether they cease during Polynesian occupation or at the onset of European arrival is unclear, but they may also have been swept up in the forces that drove the Providence Petrel to extinction.

Cats (Felis catus) arrived on the island sometime before 1795 (10) and by 1795 were plentiful enough to heavily curb the local population of rats (10). This cat population, bolstered by an abundance of rats, almost certainly worsened predation pressure on the local avifauna, and may have played a further part in the extinction of the petrels (10). It is unclear when Black Rats (Rattus rattus) arrived on Norfolk Island but arrive they did (7), another key culprit in avian extinctions as it has driven extinctions elsewhere, including on Lord Howe Island.

Pigs (Sus scrofa) are another problematic invader, by 1796 the population on the island numbered around 5000 individuals, though these were well kept in enclosures (10). Pigs are predators of nesting birds and eggs and may have proved troublesome for the Petrel colonies (10). Likewise, goats (Capra hircus) have also been implicated in the extinctions of petrels on Norfolk Island (10), because along with pigs, rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) they denude the landscape of vegetation (13). In 1814, the island was abandoned, and it appears both captive pigs and goats become feral and plentiful on the island (10). Mice (Mus musculus), Black Rats (Rattus rattus), chickens (Gallus domesticus) and feral pigeons (Columba livia) were also abundant on the island during the time of recolonization in 1825 (10). In the subsequent 2 years the feral pigs and goats were heavily reduced in population (10) limiting their impact to an 11-year time span (10).

The first terrestrial avifauna extinction following European settlement is the Norfolk Island Ground-Dove, which lacks any records from the 19th century (12), due to its potential terrestrial lifestyle this species was likely vulnerable to feline, suid and human exploitation (12).

Fig 4. Around sundown, a small group of British sailors are luring in dozens of Providence Petrels (Pterodroma solandri) using a campfire. The approaching birds are bludgeoned to death and collected for food. This follows the descriptions of hunting laid out by Medway 2002.

Terms of use: Artwork by Hodari Nundu and Commissioned by The Extinctions

The Third Wave

Whereas the extinction of the Providence Petrel and Norfolk Island Ground-Dove appear sudden, on a time scale of a few decades and was almost certainly the result of either human exploitation and/or overhunting by invasive species. the other avifauna extinctions on the island are less clear-cut. Certainly, it is possible that the same factors simply had a protracted impact on some species resulting in later extinctions. However, following the second round of European are two new factors: Large-scale habitat change and the influx of introduced avifauna.

The earliest two avian extinctions following the re-settlement of Norfolk island were the endemic subspecies of New Zealand Pigeon and the Norfolk Island Kaka, both of which are suspected to have succumbed as a result of human hunting (12). The kaka is reported to have been killed by early settlers, with the last individual reported as a captive specimen dying in London in 1851, with wild populations disappearing late in the first half of the 19th century. The disappearance of the New Zealand Pigeon is less well recorded but vanishes before the end of the century and potentially quite early (12).

The return of the settlers in 1825 marked the beginning of large-scale land changes. In the first round of settlement before the abandonment in 1814 only about 30% of the island’s forest was cleared to make space for agriculture and infrastructure, with some drainage of swamps from this period (6). This development and land clearing progressed much further after recolonization of the island in 1825 (6). Pollen records gathered at Kingston Swamp on Norfolk Island suggests a movement towards a flora dominated by introduced taxa, as well as a dramatic decrease in native shrubs and climbers, at least in the adjacency of the site (6). In addition to this, the abundance of habitat disturbed due to intensive grazing or forestry has left precious pristine habitat in the modern day.

Alongside the movement towards novel plant communities is the introduction of an abundance of bird species, which managed to establish themselves in the novel ecosystems generated by man. These newcomers arrived piecemeal, but most date to the 20th century with many common European species such as the European Greenfinch (Chloris chloris), Common Blackbird (Turdus merula), House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) and Common Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) (12). The movement towards novel ecosystems with introduced communities is likely to have placed (and still place) pressure on endemic taxa not suited for those conditions (12). This was certainly exacerbated with the influx of bird species which thrive in anthropogenic landscapes. Whether these species appear in the aftermath of local extinctions or actively supplanted native taxa is however difficult to say.

Four taxa disappeared during the 20th century, first was the Norfolk Island Starling which disappears from the record after 1923. The reason for extinction of this species is unclear. It coincides with the establishment of the common starling (Sturnus vulgaris) in the 1920s (12), but that chronology does seem optimistically close to imply causation. Other birds such as the Common Blackbird (Turdus merula) and Song Thrush (Turdus philomelos) arrived in the 1910s and could have contributed to the demise of the Norfolk Island Starling. More likely, habitat loss in conjunction with the introduced competitors and predators pushed the species to extinction. A similar causation could well be argued for the Norfolk Thrush, which likely faced competition from the same species – with a particular similarity to the Common Blackbird. Though last recorded in 1975 (3, 12), the bird is noted to have been in sharp decline since the 1930s (12), shortly after the arrival of the blackbird.

More puzzling is the disappearance of the endemic subspecies of Long-tailed Triller, which seems to have been abundant until 1941, but last recorded in 1942 (12). What brought upon this sudden shift? It is difficult to say, perhaps the claims of abundance in the years preceding the decline of the Long-tailed Triller are exaggerated, but even so the extinction remains peculiar.

The final recorded extinction is of the White-breasted White-eye. The last sighting of the species was reported in 1978/1979 (3, 12), wherein it was restricted to the area around Mt Pitt – the most forested and undisturbed part of the island (12) indicating it was a refugia for a species unable to survive elsewhere on the island. Meanwhile, an introduced congener – the silvereye (Zosterops lateralis) – is ubiquitous on Norfolk Island (12).

A fifth taxon, the Norfolk Island Boobok faced a pseudo-extinction from genetic dilution. The subspecies faced steep declines through the 20th century and by the 1970s was confined to a tiny, protected area (4). The causes of this decline has been suggested as a loss of nesting spaces due to habitat loss and taxa competing for hollows such as rats and starlings (4). By 1987 only a single female was known to survive. As a last-ditch conservation effort two male individuals of the New Zealand Boobok (Ninox novaseelandiae novaseelandiae) were introduced to the island, one of which interbred with the surviving female, producing hybrid offspring (4), which in turn have established a small population of about 45-50 individuals, derived from this original pair. Worrisomely, no successful breeding has been recorded since 2012 and the future remains uncertain (11). With a purely paternal N. n. novaseelandiae lineage and a purely maternal N. n. undulata lineage (4), the status of the new hybrid is disputed. Other endemic species remain extant but are restricted to smaller parts of the island where human impact is less keenly felt (12).

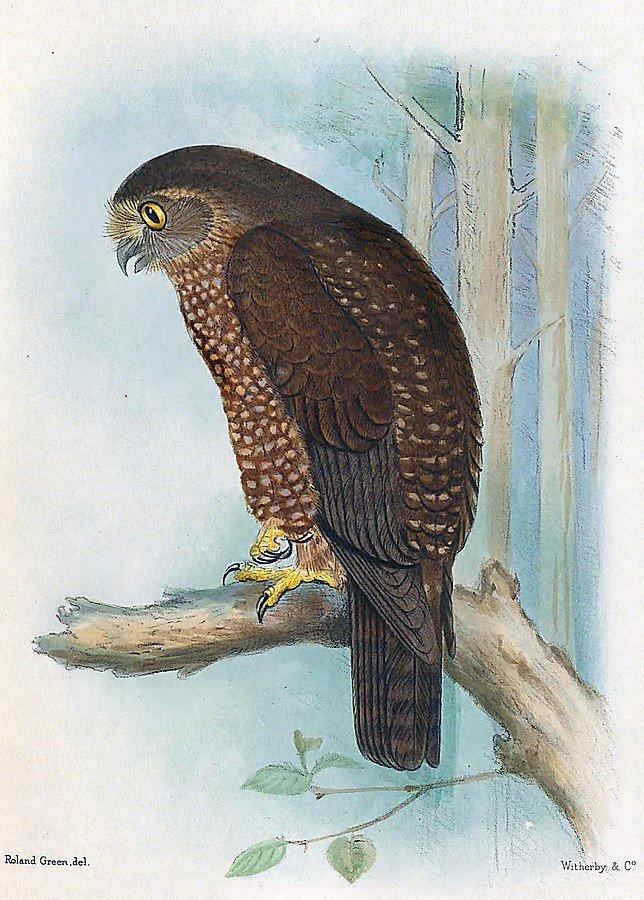

Fig 5. An illustration of the Norfolk Island Boobook (Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata) by Henrik Grønvold. This sub-species now only exists as a hybrid and is highly threatened.

Terms of Use: No Rights Reserved

Comparison & Conclusion

Norfolk Island offers an interesting case study of how initial Polynesian impact differed from that of modern European settlers and provides a well-resolved timeline of extinction. The archipelago also serves as a point of comparison to the Lord Howe Island Group, sporting similar faunas but different histories, much discussion can arise from contrasting the two. It appears that the Polynesian arrival caused the extinction of several flightless (or poorly flying) birds on Norfolk Island either via direct hunting or through the introduction of the Polynesian Rat. The endemic Lord Howe Woodhen survived where its Norfolk Island counterpart went extinct, perhaps due to the Polynesian Rat? Or was this species preferentially hunted by the Polynesians? Polynesian Rats likely drove the endemic gecko extinct on Norfolk Island where it survived on Lord Howe. Both major islands potentially have a large endemic species of Porphyrio which goes extinct following first human settlement independently of any shared invasive species, reinforcing the case for human hunting.

The plentiful Providence Petrel endemic to the two Island groups went extinct on Norfolk Island following European settlement, but not on Lord Howe. Why? Because the initial settlers of Norfolk Island harvested them in droves when Lord Howe’s did not? Perhaps. On the other hand we see striking similarities between the two as well, for example the extinction of ground pigeons and parrot species on both islands following early European settlement.

Things become increasingly muddled when heading into the late 19th and 20th centuries, because the list of pressures on Norfolk Island grows. Disentangling the effects of invasive predators, human exploitation, habitat loss and introduced competitors is near impossible when working exclusively with descriptions and extinction dates. Some introductions or events may coincide well with the extinction of a species, but it is worth asking: how long does an extinction take? Can we attribute the final demise of the Norfolk Thrush to the recent arrival of the Blackbird? or are these simply the final gasps from an earlier introduction of cats and rats? Of course, it is also overly simplistic to think of these extinctions as unicausal. Indeed, pressures may have had not only additive effects, but also exacerbate one other. For instance, the blackbird became much more plentiful on Norfolk Island than on Lord Howe because there was a large degree of habitat loss. Despite the murkiness surrounding which pressures ultimately drove extinctions, there is little doubt it was driven by human agency, directly or indirectly.

References

1. Anderson, A., Higham, T., Wallace, R. (2001). The radiocarbon chronology of the Norfolk Island. Anderson, A., White, P. (2001). The Prehistoric Archaeology of Norfolk Island, Southwest Pacific. Records of the Australian Museum, Supplement 27, 33-43.

2. Anderson, A., White, P. (2001) Approaching the Prehistory of Norfolk Island. Anderson, A., White, P. (2001). The Prehistoric Archaeology of Norfolk Island, Southwest Pacific. Records of the Australian Museum, Supplement 27, 1-10.

3. Dutson, G. (2012) Population densities and conservation status of Norfolk Island forest birds. Bird conservation International 23, 271-282.

4. Garnett, S. T., Olsen, P., Butchart, S. H. M., Hoffmann, A. A. (2011) Did hybridization save the Norfolk Island boobook owl Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata? Flora & Fauna International, Oryx, 45(4), 500-504.

5. Holdaway, R. N., Anderson, A. (2001). Avifauna from the Emily Bay Settlement Site, Norfolk Island: A Preliminary Account. Anderson, A., White, P. (2001). The Prehistoric Archaeology of Norfolk Island, Southwest Pacific. Records of the Australian Museum, Supplement 27, 85-100.

6. Macphail, M. K., Hope, G. S., Anderson, A. (2001). Anderson, A., White, P. (2001). The Prehistoric Archaeology of Norfolk Island, Southwest Pacific. Records of the Australian Museum, Supplement 27, 123-134.

7. Major, R. E. (1991). Identification of Nest Predators by Photography, Dummy Eggs and Adhesive Tape. The Auk 108 (1), 190-195.

8. Matsio-Smith, E., Horsburgh, K. A., Robins, J. H., Anderson, A. (2001). Genetic variation in archaeological Rattus exulans remains from the Emily Bay settlement site, Norfolk Island. Anderson, A., White, P. (2001). The Prehistoric Archaeology of Norfolk Island, Southwest Pacific. Records of the Australian Museum, Supplement 27, 81-85.

9. Matsio-Smith, E. (2002). Something Old, Something New: Do Genetic Studies of Contemporary Populations Reliably Represent Prehistoric Populations of Pacific Rattus exulans? Human Biology 74(3), 489-496.

10. Medway, D. G. (2002). History and causes of the extirpation of the Providence petrel (Pterodroma solandri) on Norfolk Island. Notornis 49, 246-258.

11. National Environmental Science Program Threatened Species Research Hub (2019) Threatened Species Strategy Year 3 Scorecard – Norfolk Island Boobook Owl. Australian Government, Canberra. Available from: http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/species/20-birds-by2020/norfolk-island-boobook-ow

12. Schodde, R., Fullagar, P., Hermes, N. (1983). A Review of Norfolk Island birds: past and present. Canberra: Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service.

13. Priddel, D. (2010) A Review of the seabirds of Phillip Island in the Norfolk Island Group. Notornis 57, 113-127.

14. Anderson, A., Green, R. (2001). Domestic and religious structures in the Emily Bay settlement site, Norfolk Island. Anderson, A., White, P. (2001). The Prehistoric Archaeology of Norfolk Island, Southwest Pacific. Records of the Australian Museum, Supplement 27, 43-52.

15. White, P., Anderson, A. (2001). Prehistoric settlement on Norfolk Island and its Oceanic context. Anderson, A., White, P. (2001). The Prehistoric Archaeology of Norfolk Island, Southwest Pacific. Records of the Australian Museum, Supplement 27, 136-150.

16. Schmidt, L., Anderson, A., Fullagar, R. (2001) Shell and Bone Artefacts from the Emily Bay Settlement Site, Norfolk Island. Anderson, A., White, P. (2001). The Prehistoric Archaeology of Norfolk Island, Southwest Pacific. Records of the Australian Museum, Supplement 27, 67-74.