Pachyderms, Power, and Politics: The history of the elephant in Northeastern Africa

This is a guest article, kindly contributed by Reginald O'Donoghue, a bachelors Student studying Ancient Near Eastern Studies at SOAS University in London. Reginald runs the Šar Rīmī blog, a site exploring various topics related to the ancient near east including the ecology of the region. He also runs a twitter profile @ReginaldODonog1.

Introduction

The elephant was once numerous, and politically significant in the region of Northeast Africa, for cases of convenience, defined, for the sake of the essay, as Sudan, Eritrea, and Northern Ethiopia. Now all but gone, only found in a small population in Western Eritrea, which occasionally crosses into Sudan. It’s presence in the region encouraged the spread of ancient imperialism, with the Ptolemies of Egypt seeking to use the elephants as a resource, both for their ivory, and their value in warfare. Kingdom’s rose and fell according to the fortunes of the ivory trade, and it is said that certain peoples of the region relied almost exclusively on elephant hunting.

War Elephants, some background

There is mention of the usage of elephants in warfare in the annals of Neo-Assyrian king Aššurnaṣirpal II [Aššurnaṣirpal II 030, 95], who mentioned receiving five live elephants as tribute from the governors of the provinces of Sūḫu and Lubdu. The king mentions taking these elephants with him on ‘campaign’ (Gerri).

5 pīrī balṭūtī maddatu ša šakin māti sūḫi ū šakin māti Lubda lū amḫur. Ina gerri ittiya ittanallakā.

Five live elephants as tribute from the governor of the land Suḫu and the governor of the land Lubda I verily received. On campaign with me they went.

At this time, any ‘tamed’ elephants would be Indian Elephants, in this case, possibly of the Syrian variety. Whether or not the elephants were used for fighting, or merely as a display of royal power is hard to tell from this brief reference alone. Earlier remains of the Syrian Elephant found at Qatna in Syria seem to have been taken as trophies, symbols of royal power [Pfälzner, 2016].

Be that as it may, by the Achaemenid era, elephants were certainly used in warfare in the near east [Lobban & de Liedekerke, 2000], their usage among western powers exploded after the death of Alexander the Great, when the region was carved up amongst his generals Seleucus (based in Mesopotamia) and Ptolemy (based in Egypt). Seleucus’ dynasty, the Seleucids, controlled the land routes to India, and thus could import a steady supply of Indian Elephants, the first in the Near East since the 9th or 8th century. Despite their mixed record in combat, elephants were highly valued weapons, perhaps for ‘psychological reasons’ as a means of instilling fear and panic, or alternatively, as a demonstration of royal power. The Ptolemies, therefore, wished to have a supply of war elephants themselves, to compete against their rivals, the Seleucids [Burstein, 2021].

Cut off from land-based trade with India, the Ptolemies fortunately had a population of elephants to the south of them in Sudan, known to the Greeks as Ethiopia.

The Red Sea Elephant

Extinct in Egypt since the Old Kingdom period, the regions to the south, in what is now Sudan and Eritrea, which the Egyptians referred to as ‘Kush’ (often anachronistically called ‘Nubia’ in the modern era) and ‘Punt’ retained a large population, large enough to be of interest to the Ptolemies in the late 1st millennium BC. The elephant seems to have played an important role in Kushite culture, as can be seen from the artwork depicting the creatures found at the Kushite site of Musawwarat es-Sufra in Sudan. The ancient name of this town, Aborepi, is derived from the Meroitic word for ‘elephant’, abore [Haaland 2014: p665]. Speculative attempts have been made to identify an ‘elephant training camp’ at Musawwarat es-Sufra, however, these claims (based on the presence of ramps in the archaeology) are doubtful. Nonetheless, the testimony of Kushite art shows that the

elephant had been tamed by the people of the region, perhaps with the help of Indian mahouts [ibid]. A relief [Fig. 1] at Musawwarat es-Safra shows a kingly figure riding on the back of an elephant, as does an (unprovenanced) bronze statuette displayed at the Nubia Museum in Aswan, Egypt. These depictions occur in a ceremonial or ritual context, rather than a military context [Charles, 2018], yet still display evidence for the taming of the elephant by Kushites.

Fig. 1. A Meroitic royal figure riding an elephant, from a relief at Musawwarat es-Safra. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269278631_The_Meroitic_Empire_Trade_and_Cultural_Influences_in_an_Indian_Ocean_Context/figures?lo=1

A steady flow of ivory from Kush and Punt to Egypt (and further, to the Near East and Mediterranean) had always existed, the tomb of the 18th century vizier Rekhmire shows Kushites and Puntites (alongside others) carrying ivory as tribute [Lafrenz, 2004: p39]. Nonetheless, in the Hellenistic era, new value was given to the animals alive.

The ’arms-race’ for the elephant was, it seems, the main driver of Ptolemaic expansion into what is now Sudan, both from the Nile valley, and from Red Sea colonies such as Ptolemais of the Hunts, now Aqiq in Sudan [Burstein, 2021]. Ptolemy III also set up a stela in Adulis in Eritrea, which the Christian traveller Cosmas Indicopleustes copied down. In it, he describes his elephant hunting exploits in the region,

Great King Ptolemy… led an expedition into Asia with… elephants from Troglodytis and Ethiopia. These animals his father and he himself hunted out from these places and brought to Egypt for use in war

[Bowersock, 2013: p35]

Troglodytis is the land of the Troglodytae, a people said by the geographer Strabo to live between the Nile and the Red Sea. They are said by Pliny the Elder to have made their living exclusively from hunting elephants [ibid: p39]. Perhaps an exaggeration, but still a testament to the great importance and fame which elephants had in the region. Ethiopia is, of course, not the modern country, nor is it a generic term for ‘sub-saharan’ Africa, but rather seems to refer to a specific place, as opposed to Troglodytis, perhaps the Kingdom of Kush, often referred to as ‘Ethiopia’ in Greek sources (e.g., Herodotus refers to Kush’s capital, Meroë as the ‘mother city of the whole of Ethiopia’) as in the famous New Testament story of the ‘Ethiopian Eunuch’, who was a servant of the Kandake of Kush (Acts 8:26).

The desire to exploit new elephant populations led to greater exploration of the interior of Africa by the Greeks. For the first time, the Greeks had an accurate knowledge of the source of the Nile and were forced to narrow down the extent of the supposedly impassable ‘torrid zone’ between the tropics and the equator, as it became clear that the interior of Africa was inhabited [Burstein, 2021].

The elephant arms race culminated at the battle of Raphia, near Gaza, in 217 BC, between Ptolemy IV Philopater of Ptolemaic Egypt, and Antiochus III of the Seleucid empire, where African Elephants met Indian Elephants in battle. Here, the historian Polybius tells us,

…most of Ptolemy's animals, as is the way with Libyan elephants, were afraid to face the fight: for they cannot stand the smell or the trumpeting of the Indian elephants, but are frightened at their size and strength, I suppose, and run away from them at once without waiting to come near them…

Plb. 5.84

Polybius’ account that the ‘Libyan’ (African) elephants were ‘frightened at the size and strength’ of the Indian Elephants implies that they were smaller than Asian Elephants. This has led to speculation by historians that the elephants of Ancient Northeast Africa were in fact a population of African Forest Elephants (Loxodonta Cyclotis), as opposed to the much larger African Bush Elephant (Loxodonta Africana). However, genetic evidence suggests that the modern-day elephants on the Eritrean/Sudanese border (more on them later) are in fact African Bush Elephants, related to populations elsewhere in East Africa [Brandt et al, 2014]. It is possible that Polybius was confused or relying on folklore. It is also possible that populations of Forest Elephants did indeed live in some parts of Sudan, or that the elephants of Sudan were a small-bodied breed of Bush Elephants. Ultimately, it is unclear as to the nature of the elephants in Polybius’ account.

Fig 2. Map of sites mentioned in text, as well as the extant and possibly extinct range of Elephants in North-East Africa, according to IUCN Data.

Terms of use: Own Work

Elephants in Late Antiquity

Despite the heavy exploitation, the elephant (albeit much depleted) survived in the region of Sudan and Eritrea. The era of the war-elephant craze in the near east ultimately lasting little over a century [Pankhurst, 1996], the Seleucids had lost control of the land routes to India, and the Ptolemies had depleted the nearest stocks of elephants [Cobb, 2016]. It continued however, in India, and perhaps also in Sudan and Ethiopia. The rise of the Ethiopian kingdom of Aksum, and its port of Adulis (perhaps originally a small ivory trading centre) can perhaps be explained by the decline of Hellenic interest in elephants, allowing Aksum to have a monopoly over the ivory trade [Charles, 2018]. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea certainly emphasises the economic importance of ivory to the kingdom of Aksum. Whilst they clearly survived in large numbers (see below), evidence for elephants at all in Northeast Africa during this period is, however, scant. Indeed, the standard Ge’ez (Ethiopic) word for ‘elephant’ (Nage) seems to be a Sanskrit loanword, perhaps indicating that the Ethiopians imported elephants, or (more likely) mahouts from India, perhaps due to the region’s greater skill at training. The Byzantine Christian traveller Cosmas Indicopleustes, who had travelled to the Aksumite empire in Ethiopia in the 5th century AD noted that the Ethiopians were less skilled in taming the elephant than the Indians, though nonetheless would capture and train young elephants (presumably local African Elephants) ‘for show’. Nonnosus likewise claims that King Kaleb of Aksum had a chariot pulled by elephants [Pankhurst, 1996]. Nonnosus, as a Byzantine ambassador to Aksum, is presumably a reliable source.

Whilst (as Cosmas’ reference shows) the Aksumites apparently did capture and train local elephants (perhaps also relying on imported Indian Elephants), whether the elephant was used in warfare, however, is a matter of dispute. An inscription from the reign of Aksumite king Ezana (famous for his conversion to Christianity) mentions a military cohort known as the sarwē dākēn, possibly cognate to the Saho word dakano, and the Amharic zahon, both meaning ‘elephant’ [Charles, 2018; Pankhurst, 1996]. This is, however, speculative. Crude rock art from Aksumite controlled Yemen (see below) also shows mounted elephants [Charles, 2018]. By far the most explicit mention of Aksumite war elephants, however, comes from Medieval Islamic sources.

In the 6th century, King Kaleb of Aksum invaded the Jewish kingdom of Himyar in Yemen, overthrowing its king, Yusuf, remembered in medieval Arab texts as Dhu Nuwas (possessor of the sidelocks), who had been brutally persecuting Christians. Ultimately, control over Yemen was taken by an Aksumite general, Abraha, who made himself king.

Abraha is remembered in the Islamic tradition as invading the Hijaz and attempting to destroy the Kaaba in Mecca. Accounts of his campaign involve war elephants, including the famous elephant named ‘Mahmud’ by Ibn Kathir, who, in the accounts of Muslim historians, refused to march on Mecca, and would only prostrate himself [Charles, 2018]. These accounts of the ‘Year of the Elephant’ originate from commentary on the Qur’an itself, specifically Surah 105:

Have you not seen how your Lord did with the companions of the elephant? Did He not make their plot go astray? He sent against them birds in flocks – (which) were pelting them with stones of baked clay – and he made them like chewed-up husks

Whilst classical exegetes held that this refers to Abraha’s campaign, some modern scholars, such as Daniel A Beck, and (following him) Gabriel Said Reynolds instead suggest it refers to events recorded in the Books of Maccabees, where elephants are similarly defeated through the power of God, due to the apparent lack of evidence for the use of African Elephants in warfare after the 1st century BC [Reynolds, 2018: p929]. Consider, the events of III Maccabees, for example, where Ptolemy IV unleashes a cohort of elephants (which presumably were of Northeast African origin themselves) drunk on wine and incense on a crowd of Jews bound in fetters in a hippodrome. The Jews cry out to God, and angels descend from heaven, attacking the enemy troops, and causing the elephants to turn around and destroy the Ptolemaic army. (One wonders if this story is a Jewish reflection of the poor performance of the very same Ptolemy’s elephants at the aforementioned battle of Raphia, mentioned in chapter I of the book)

Likewise, in II Maccabees 15, Judas Maccabaeus faces the army of the Seleucid general Nicanor, which includes a cohort of war elephants. Recognising the overwhelming odds, Judas prays to God, asking him to send an angel, like the one which destroyed the army of Assyrian Sennacherib during the 701 BC siege of Jerusalem. God answers his prayer, and Nicanor’s army is defeated, with Nicanor killed.

Note, that the Arabic word in Surah 105 translated as ‘bird’ can infact refer to any flying creature, such as an angel. Whilst the story does not follow either of the Maccabean accounts exactly, it is worth noting that the Qur’an’s sacred history rarely corresponds exactly to biblical traditions. For example, a figure known as Samiri is responsible for the sin of the golden calf in the Qur’an, rather than Aaron, brother of Moses, as in the Bible.

However, as discussed before, rock art depicting ridden elephants has indeed been discovered in Yemen. Though the date of the art cannot be determined for certain, the reign of Abraha seems like a plausible context for it, given the already existing tradition surrounding his usage of war-elephants. Though the Sassanid Persians, who ruled Yemen after Abraha are known to have used war elephants, they are not known to have done so in Arabia [Charles, 2018]. As to the nature of these elephants, whilst the Aksumites are not known elsewhere to have used elephants in war, and indeed were less skilled than Indian mahouts, the difficult logistics alone would make an importation of Bush Elephants from across the Bab El Mandeb much more plausible than the importation of Indian elephants from South Asia.

The reasons for the relative absence of elephants in Aksumite records must elude us, for according to the 6th century Byzantine historian, Nonnosus, they were very numerous in the kingdom of Aksum, when he visited in the 530s, occurring in herds of around 5000. He also stated that "It was not easy for any of the locals either to approach [the elephants] or to chase them off the pasturage", which has caused some modern scholars to infer that the Aksumites had a policy of elephant conservation. This is probably not what Nonnosus intended [Charles, 2018], more likely, he merely refers to the difficulty in driving away elephants, especially when occurring in such large numbers. Nonetheless, by the Aksumite period, elephants (and rhinoceroses) were already rare (albeit not absent) in the coastal regions, with the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea saying,

Practically the whole number of elephants and rhinoceros that are killed (in the kingdom of Aksum) live in the places inland, although at rare intervals they are hunted on the seacoast even near Adulis.

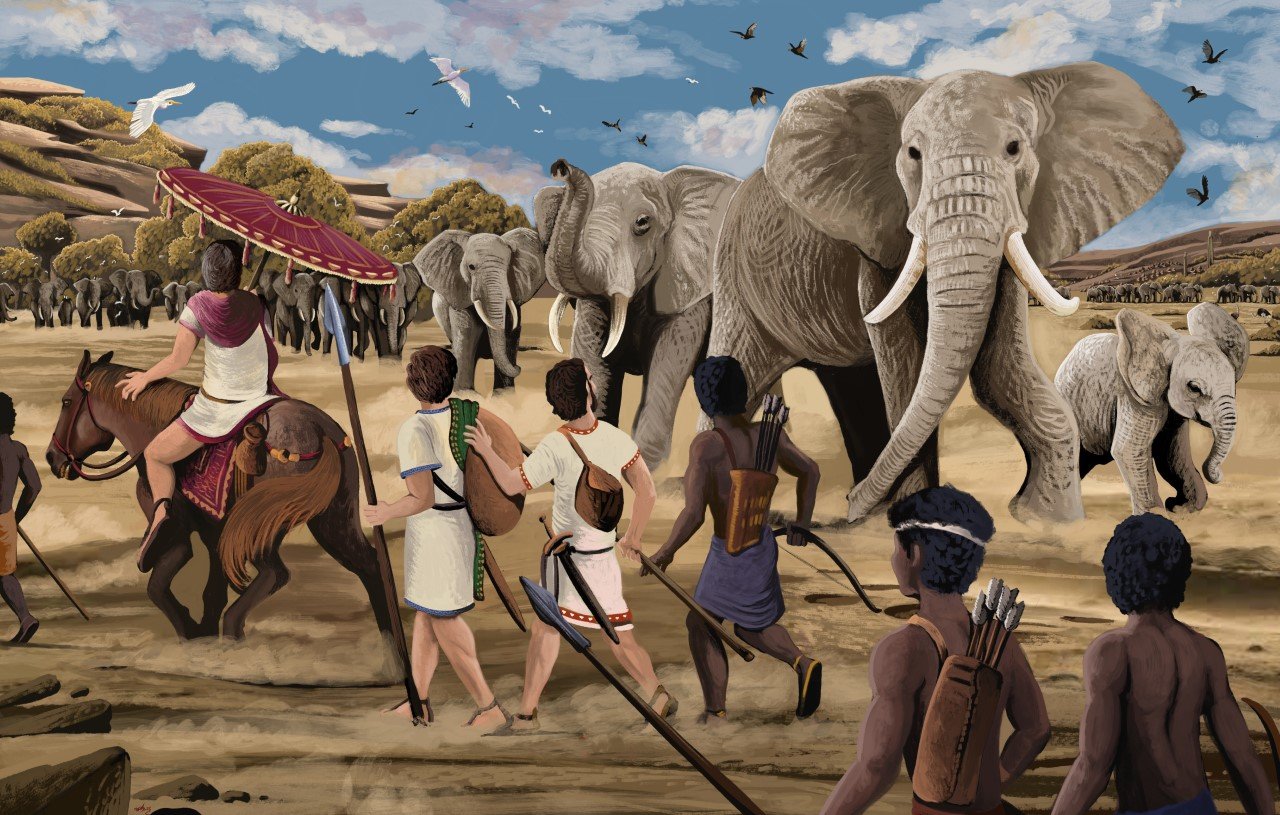

Fig 3. Greek travelers in the kingdom of Aksum, alongside their local escort, encountering a large herd of African bush elephants (Loxodonta africana) in 6th century Ethiopia.

Terms of use: Artwork by Hodari Nundu and Commissioned by The Extinctions

The Last Elephants

Environmental conditions may have played a role in the decline of elephant populations in the region, alongside the heavy influence of humans. According to palaeoclimatic studies, less rainfall began to penetrate the Sahara from the south in the 1st millennium AD. Populations of desert adapted elephants do exist in Mali and Namibia, yet these are the exception to the rule. Elephants are browsers who require a large amount of vegetation. Human caused environmental degradation, through iron production has also been suggested as a cause both for the decline in the ecology of Sudan, as well as the power of the kingdom of Kush. Iron production, which Kush, and it’s capital Meroë was famous for, being known as the ‘Birmingham of Africa’, would require a large amount of wood for smelting, leading to deforestation of the Acacia forests of Sudan. However, truly, little evidence for such deforestation exists. One study [Humphris, 2019] concludes that the plant ecology of Sudan has truly changed very little. The Kushites would overwhelmingly smelt with Acacia nilotica wood, from a tree that regrows very quickly, often becoming invasive.

Until 2001, the elephant was presumed extinct in Eritrea, as a victim of the war of independence from Ethiopia. This changed however, with the discovery of the small herd in the Gash-Barka region in 2001. Though much depleted from millennia of human activity (and apparently suffering evidence of inbreeding), this ancient and fascinating elephant population has not only survived but seems to be growing in number. In Sudan, no confirmed sightings of the elephants had been made since the 1960s, despite the discovery of footprints in 2012. This changed, however, in 2019, when photographic evidence of an African elephant was taken by a Sudanese customs officer [Fig. 3], confirming the presence of the elephant, perhaps through migration from Eritrea.

Conclusion

Of great importance to the ancient kingdoms of Kush, Aksum and Ptolemaic Egypt, the African bush elephant was once very numerous in the region of Sudan, Eritrea and Northern Ethiopia, its presence determining the course of geopolitics in the region in ancient times. Once believed extinct, the elephants of the region are much depleted in number, and yet continue to cling on. A revival of their numbers and range seems underway, and with adequate conservation, the elephants of Northeast Africa may yet thrive once more.